Historical Lessons for State Department Reform

By: Sophia Brown-Heidenreich | June 12, 2023

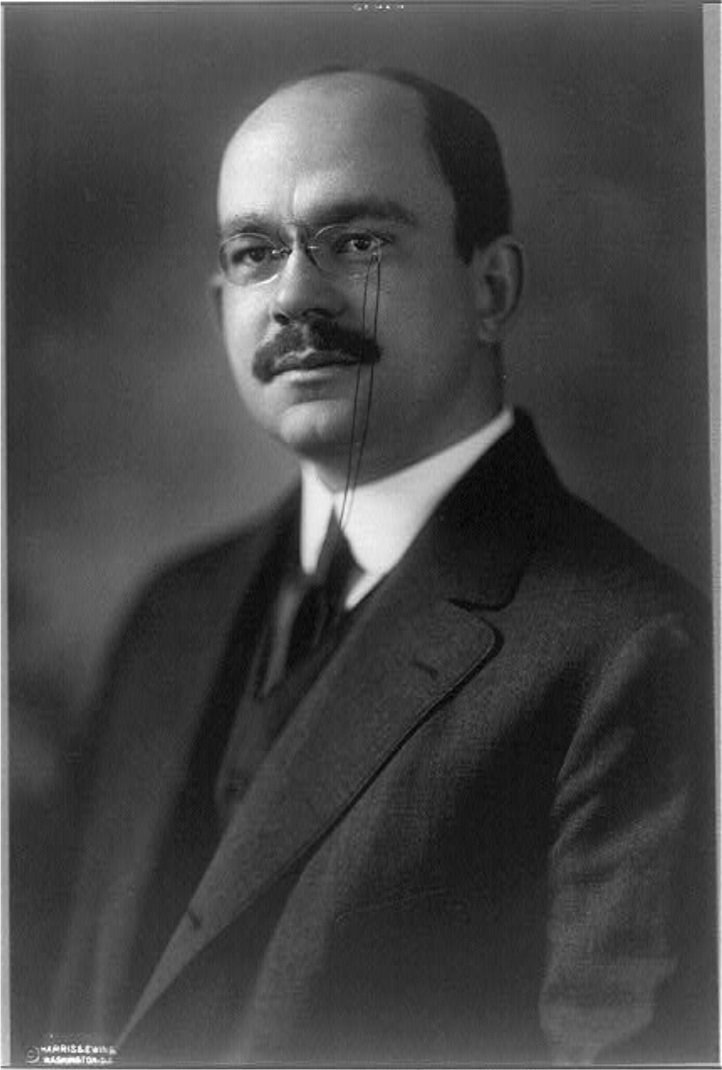

U.S. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographic Division

“Let us strive for a foreign service which will be flexible and democratic; which will attract and retain the best men we have; which will offer reasonable pay, reasonable prospects for promotion, [and] reasonable provision against want when old age comes to a faithful servant.”

-Rep. John Jacob Rogers, 1923

Next year, the State Department will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Rogers Act, one of the most consequential pieces of legislation in its storied history.

The law,¹ which was signed in 1924, replaced the State Department’s spoils system, under which successive administrations hired their political supporters, with merit-based hiring and promotion. The bill professionalized American diplomacy and significantly impacted the department, including by paving the way for women and Black diplomats to enter the Foreign Service. It sought to dramatically reduce political appointees, create fair standards for advancement, and structure the Foreign Service to allow for flexible staffing. It also combined the Diplomatic and Consular bureaus into a single unified Foreign Service.

The Rogers Act paved the way for the American diplomatic service to become one of the world’s most influential. Yet many of the problems that the Rogers Act sought to address a century ago have reawakened in today’s State Department: struggles with meritocracy, worrisome politicization, and a siloed personnel system.

Interest in comprehensive State Department reform is growing. Congressional leaders passed legislation to launch a Commission to Reform the State Department.² The Commission still requires appropriations³ to begin its work, but its initial passage is indicative of renewed legislative interest in upgrading the State Department. Meanwhile, Secretary of State Antony Blinken is leading a high-profile modernization effort⁴ from within the Department.

The history of the Rogers Act offers lessons for how today’s reformers may succeed or fail. Several important ingredients for passing successful reform emerged from our review:

Unrelenting government insiders led the push for reform.

Pressure from civil society was vital.

Crises brought systemic problems into focus.

Close collaboration between the executive branch and Congress ensured viable legislation.

Support from high-ranking officials helped with smooth passage, but buy-in from the State Department’s workforce was also necessary.

As the story of the Rogers Act shows, successful reform is not simple or straightforward. It required the dedication of a broad team. Let’s review the history.

¹ https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/43/STATUTE-43-Pg140.pdf

² https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3491/text

³ https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58062

⁴ https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-on-the-modernization-of-american-diplomacy/

The Early State Department: “Rich Men or Rogues”

By 1924, the State Department had developed a reputation for inefficiency, nepotism, and corruption, which the Rogers Act sought to address. A combination of poor internal organization, low pay, political favoritism, and lax oversight contributed to ever-worsening conditions within the Department.

Part of the problem lay in an organizational structure that was a remnant of the previous century. Congress entrusted the State Department, established in 1789 as the first executive agency, with a variety of domestic and international responsibilities: conducting the census, manning the mint, keeping government-wide records, and managing political and economic affairs abroad. In 1833, Secretary of State Louis McLane organized the Department into bureaus to better handle its sprawling tasks. Only two of the original six State Department bureaus handled foreign affairs: the Diplomatic Bureau and the Consular Bureau.

The Diplomatic Bureau handled political negotiations, while the Consular Bureau oversaw trade and commerce. Before the Department of Commerce was established in 1903, this distinction between diplomatic and consular activities may have made sense. But the two bureaus operated in isolation from one another, even as rising globalization blurred the line between these two areas of foreign policy. Then, as today, bureaucratic structures were unable to adapt to rapid external changes.

Another problem stemmed from budget constraints. During the 19th century, the State Department struggled to cover the costs of expanding overseas operations. To maintain the steady expansion of diplomatic and consular representation, the Department hired many consular officers but paid them very low wages. To supplement their income, consular officers pocketed substantial profits generated from fees for their services.⁵

But in 1856, Congress forbade this practice and required all fees to be handed over to the Treasury. Marginal wage increases seldom covered living expenses. When the famed novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne left his consular post at Liverpool in 1857, he commented that his successor would have to be “a rich man or a rogue” to endure the new compensation structure.⁶

Indeed, rogues were common. The State Department’s Consular Bureau became known for criminal behavior in the decades to come. An 1872 investigation into the consular service revealed that officers were collecting illegal fees, issuing illegal passports, and committing fraud on a mass scale. Lead investigator De Benneville Randolph Keim spoke of the “ingenuity displayed by consular officers, since the Act of 1856 particularly, in defrauding the Government and grasping gains from various outside sources.”⁷

The Diplomatic Bureau also earned a bad reputation. Though diplomats held the more prestigious positions, they were typically seen as decadent and ineffectual. Hugh S. Gibson, minister to Poland in 1924, described diplomats as “the boys in the white spats, the tea drinkers, the cookie pushers … the specimens who have become poor imitations of foreigners.”⁸ American diplomats in the UK had spent so much time in London that they reportedly started dressing like nobility and speaking in British accents.

⁵ Charles Stuart Kennedy, The American Consul: A History of the United States Consular Service, 1776-1914 (Greenwood Press, 1990), 22.

⁶ 1. A. Turner, Nathaniel Hawthorne: A Biography (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1980), 274.

⁷ Quoted in: Office of the Historian, “Problems in the Consular Service,” U.S. Department of State, accessed March 20, 2023, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/problems.

⁸ Quoted in: Jim Lamont and Larry Cohen, “In the Beginning: The Rogers Act of 1924,” Foreign Service Journal 91, no. 5 (May 2014): 26–32, https://doi.org/https://afsa.org/sites/default/files/fsj-2014-05-may.pdf.

Inching toward Comprehensive Reform

The spoils system afflicted both the Diplomatic and Consular bureaus, as well as the rest of the U.S. government. With every election, successive presidents replaced much of the civil service with cronies. This meant that executive branch staff tended not to be committed experts but political supporters of the incumbent party.

The biggest step in undoing the spoils system was the Pendleton Act of 1883, which required competitive exams for federal employees and prohibited the dismissal or demotion of bureaucrats on political grounds. The Pendleton Act sought to create a class of expert staff who served the government rather than its temporary political leadership.

Public support for this reform arrived with a crisis: the assassination of President Garfield at the hands of a campaign supporter who had been denied a spoils position as the consul in Paris. Though the murderer was motivated by a staffing ay the State Department, the Pendleton Act did not apply to the diplomatic and consular corps because it exempted Senate-confirmed appointments. Clerks at the State Department became subject to examinations, but most of the rest of the Department remained exempt from merit requirements.

Despite the omission of the Consular and Diplomatic bureaus from the Pendleton Act, successive presidents made some attempts to expand merit requirements to the State Department. Grover Cleveland was the first to set out requirements for a meritocratic entrance exam for consular officers in 1895. But two years later, William McKinley all but undid the exam requirement by making it a mere formality for his hand-picked appointees.⁹ During his presidency, only a single applicant failed the test.¹⁰

By the early 20th century, the United States had undergone a shift in its politics, leading to support for government reform on all levels. Activists pushed to eliminate corruption and address the worst excesses of rapid industrialization. They saw increases in state capacity as an antidote to these ills.

Reformers soon turned their attention to the State Department. In 1905, Theodore Roosevelt appointed Elihu Root as Secretary of State, calling him “the ablest man that has appeared in the public life of any country, in any position, in my time.”¹¹ In his previous position as Secretary of War, Root reorganized the War Department, establishing a General Staff for improved planning and coordination, restructuring the National Guard, and founding the Army War College. Root sought similar improvements in his new position as Secretary of State.

Animated by the expansion of U.S. commercial power, Root focused first on reforming the Consular Bureau. In 1906 he wrote:

I got very much disturbed by the condition of the consular service. It had become merely a means of doing two things; one was rewarding political service and the other was to enable a man whose power in the government was worth regarding, to get rid of a competitor. If a man was making trouble, the best way to get rid of him was to get him a place as a consul.¹²

That year, Root worked together with the head of the consular office and Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA) to pass the Reorganization Act of 1906. The bill introduced consistent salaries across nine grades and mandated regular inspections of consular offices for increased accountability.

To the great disappointment of Root and his allies, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee struck from the bill provisions requiring competitive examinations and promotion based on merit. The examinations were assumed to be unconstitutional, and reformers worried that the clause would tank the entire bill.¹³ Presidents William Taft and Theodore Roosevelt addressed this omission via executive order, setting up competitive civil service examinations for entry-level officers and establishing a Board of Examiners for hiring and promotion.¹⁴

But all the aforementioned reform efforts only concerned the Consular Bureau, leaving the Diplomatic corps virtually untouched. The State Department still suffered from budget constraints and the effects of an ad-hoc personnel system that developed during the 19th century. Poor pay, a lack of retirement and disability benefits, and the absence of home leave allowances were sources of frustration within diplomatic ranks. Another major problem for retaining talent was that diplomats promoted to ministers were not guaranteed a return to the diplomatic corps after their term ended. This led to a systematic loss of the most accomplished professionals in the Department.

The new century called for a new State Department.

⁹ Thomas G. Paterson, “American Businessmen and Consular Service Reform, 1890’s to 1906,” Business History Review 40, no. 1 (1966): 77–97, https://doi.org/10.2307/3112303.

¹⁰ Office of the Historian, “A New Professionalism,” U.S. Department of State, accessed March 20, 2023, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/professionalism.

¹¹ Quoted in: Richard Hume Werking, The Master Architects: Building the United States Foreign Service 1890-1913 (Lexington, KN: University Press of Kentucky, 1977), 91.

¹² Philip C. Jessup, Elihu Root, vol. 2 (New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1938), 101.

¹³ Werking, The Master Architects, 96.

¹⁴ Office of the Historian, “Administrative Timeline of the Department of State: 1900–1909,” U.S. Department of State, accessed February 28, 2023, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/timeline/1900-1909.; “Executive Order 1143 of November 26, 1909, Regulations Governing Appointments and Promotions in Diplomatic Service,” https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Executive_Order_1143.

The Winning Strategy

Many stars had to align to achieve comprehensive personnel reform. Modernizing the Department required expanding competitive entry exams and rigorous promotion evaluation to diplomats and consuls, fusing the two corps, and increasing salaries and benefits—a heavy lift.

Success required internal and external advocates for State reform, a strategy to quiet opposition within the bureaucracy, and the support of leadership in both the legislative and executive branches.

Reform needed advocates in both State and Congress. The brain behind the Rogers Act was Wilbur John Carr, then Director of the Consular Bureau. Neither a rich man nor a rogue, Carr was a talented bureaucrat who earned the deep respect of his peers. Carr had long involved himself in reform efforts, convincing Root and Lodge to champion consular reform legislation in 1906—legislation that Carr largely ghostwrote.¹⁵ But Carr had his eyes set on a more comprehensive modernization of the Department. He cultivated a relationship with a fellow Massachusetts resident, Rep. John Jacob Rogers. In 1919, Rogers introduced his first legislation on foreign service reform—again ghostwritten by Carr¹⁶—but the bill never reached the floor for a vote.¹⁷ Rogers tried again the next year in 1920, as well as in 1921 and 1922, but the legislation died in committee each time.¹⁸

Rogers and Carr needed a broader coalition. Carr had whipped consular officers into supporting reform as head of the Consular Bureau, but next he needed to convince the less-sympathetic Diplomatic Bureau.

Advocating for passage of the Rogers Act in the New York Times on December 24, 1922, Rogers wrote:

A system may fall short of success either because the system itself is wrong or because its administration is wrong. Our trouble has been with the system—which fundamentally has remained unchanged since before the Civil War. The administration of the system seems to me remarkably skillful considering the impediments in the way. But reorganization and modernization are the order of the day in every governmental activity. The time has come—and the American businessmen and students, as well as many others, realized that it has come—for a thorough overhauling of our foreign service.¹⁹

But some remained unconvinced. Skepticism from diplomats came in several flavors. Some seemed intent on protecting their privilege and patronage. William Richards Castle Jr, chief of the Bureau of Western European Affairs, said, “No man … not possessed of a large income” should be admitted to the foreign service.²⁰ Others, like Undersecretary of State Joseph Grew, favored increased professionalization of the diplomatic corps but viewed the combination of the Diplomatic and Consular Bureaus as counterproductive.

To work against this internal opposition from diplomats, Carr and Rogers summoned support for the initiative from high-ranking State Department and administration officials. They secured endorsements from Secretaries of State Lansing and Hughes, undersecretaries and ambassadors, and President Harding followed by President Coolidge.²¹ They also received support from outside organizations, including the American Federation of Labor. Allegiance from those who served in the Department or represented its interests lent credibility to their effort.

But Congress was another matter. While debate in the House and Senate Foreign Relations Committee was minimal, State Department authorization was not a major priority.²² To bring the bill to the Senate floor for a vote, Carr and Rogers needed unanimous consent. But it faced opposition. Rep. Ross Alexander Collins said, “imagine placing a consul in a diplomatic clerkship! He is unfitted for such a place.” They could not find a single Senator to bring the motion to the floor, and thus the bill died.

One year later, Carr and Rogers tried again. This time, they secured Senate consideration with the help of Henry Cabot Lodge, who had supported Consular reform a decade earlier. Though the historical record has gaps, it is likely that Rogers and Lodge engaged in an even greater persuasion campaign with their colleagues than they had in previous cycles. The House and Senate were generally divided over whether the reform measures went too far or not far enough, but Rogers and Carr repeatedly stressed the need for reform—however imperfect—given the dilapidated state of the Department. Congress finally relented. After the Rogers Act passed with four sizable amendments, President Calvin Coolidge signed it into law on May 24, 1924. Rep. Rogers died less than a year later, but his legacy endured as “the father of the Foreign Service.”

The Rogers Act sought to create a meritocratic, cohesive workforce to strengthen diplomatic performance. It included:

Requirements for merit-based hiring examinations and merit-based promotion.

Combination of the Diplomatic and Consular Bureaus and movement of personnel between the two branches.

The creation of the Foreign Service in 9 classes with tiered pay. Ranging from $3,000 to $9,000 (or $53,000 to $159,000 in today’s dollars), the pay is roughly equivalent to current salary ranges.²³

The introduction of the extant rotation system for Foreign Service Officers and a three-year cap on terms served abroad.

Funding for regular home leave and allowances.

The establishment of the Foreign Service retirement fund, offering pensions to officers who have served more than 15 years.

Permission for officers who became chiefs of mission to remain part of the Foreign Service.

Transformation of the Wilson Diplomatic School into the Foreign Service School, the precursor to the Foreign Service Institute.

¹⁵ Lamont and Cohen, “In the Beginning.”

¹⁶ Lamont and Cohen, “In the Beginning.”

¹⁷ To amend an act entitled “An act for the improvement of the foreign service”, HR 2709, 66th Congress, 1st sess., Congressional Record 58, pt. 9: 9734, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Congressional_Record/AWlk7OIsTEMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=H.+R.+2709+%22An+act+for+the+improvement+of+the+foreign+service%22&pg=PT27&printsec=frontcover.

¹⁸ For the reorganization and improvement of the Foreign Service of the United States, HR 11058, 66th Congress, 2nd sess., Congressional Record 59, pt. 1: 387, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Congressional_Record/9h0xl9PqKEcC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=H.%20R.%2011058%20-%20%22For%20the%20reorganization%20and%20improvement%20of%20the%20Foreign%20Service%20of%20the%20United%20States%22; For the organization and improvement of the foreign service of the United States, HR 2277, 67th Congress, 2nd sess., Congressional Record Appendix and Index 61, pt. 9: 411, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Congressional_Record/9h0xl9PqKEcC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=H.%20R.%2011058%20-%20%22For%20the%20reorganization%20and%20improvement%20of%20the%20Foreign%20Service%20of%20the%20United%20States%22; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs, HR 12543: For the reorganization and improvement of the foreign service of the United States, and for other purposes, HR 12543, 67th Congress, 4th sess., 1933, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Foreign_Service_of_the_United_States/MgwNAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

¹⁹ John Jacob Rogers, “Foreign Service Neglected Study,” New York Times, December 24, 1922.

²⁰ Lamont and Cohen, “In the Beginning.”

²¹ For the reorganization and improvement of the foreign service of the United States, and for other purposes, HR 6357, 68th Congress, 1st sess., Congressional Record 65, pt. 8: 7561-7565.

²² For the reorganization and improvement of the foreign service of the United States, and for other purposes, HR 6357, 68th Congress, 1st sess., Congressional Record 65, pt. 8: 7565.

²³ “CPI Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.; “FS Salary Schedules” (Washington DC: U.S. Department of State, 2023).

Amending Mistakes

As soon as the Rogers Act was enacted, its new provisions came under scrutiny. In the process of merging the diplomatic and consular corps, inequities in promotion rates arose.

The system devised under the Rogers Act heavily favored diplomats over consuls—a problem Congress had foreseen. Though State reviewed its decision-making and offered retroactive promotion to an additional 44 consuls, when Congress discovered the unfairness in 1926, it launched an investigation into the matter. After hearings were held in 1928, it became clear that new legislation was needed to remedy the fundamental problem.

Congress responded by passing the Moses-Linthicum Act of 1931, which imposed more impartial promotion processes and reorganized the Board of Foreign Service Personnel under a new Assistant Secretary for Personnel. Congress also made various changes to the State Department’s salary bands, post allowances, sick leave, retirement, and career status for clerks in the Foreign Service. Though the onset of the Great Depression paused these changes for four years, once the economy recovered, the State Department stepped into a new era of more meritocratic and effective personnel management. The State Department developed a reputation as an excellent place to work, and attrition rates in the Foreign Service trended impressively low.

Reflecting on the Legacy of the Rogers Act

The story of the Rogers Act could have ended in 1923. If not for a highly motivated coalition of State Department and Congressional reformers, inertia would have stopped reform in its tracks.

One can draw a number of tentative lessons from this history:

Congress, not the executive branch, is the key to lasting reform.

Voters may demand reform only in the wake of a crisis, but it is the responsibility of dedicated reformers to be prepared to meet that moment.

Institutions resist reform.

Big legislative changes may be imperfect, but successive fixes are possible and seem easier to pass.

Reform can take many years to advance even when clear problems are identified.

History rhymes. Many of the problems attended to in the Rogers Act have slowly resurrected themselves over time.

It has now been more than four decades since the last major State Department reform, even as the geopolitical, technological, and economic landscapes have dramatically changed. By comparison, after the Rogers Act passed, the State Department saw further major congressional reforms in roughly 25-year increments—in the Foreign Service Acts of 1946 and 1980.²⁴ The Rogers Act responded to changing global affairs after the World War I, and its successors modernized the Department to meet the challenges of the post-World War II and Cold War eras.

The United States finds itself in a fundamentally new period of international relations, and many onlookers are again calling for a reexamination of American diplomacy, including Congress itself.²⁵ The Foreign Service must adapt.

The 100th anniversary of the Rogers Act is an opportunity to celebrate a century of American diplomatic achievements. Understanding the confluence of factors that led to the passage of the Rogers Act will help us extend this legacy for another 100 years.

²⁴ Office of the Historian, “Landmark Departmental Reform,” U.S. Department of State, accessed March 1, 2023, https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/reforms.

²⁵ U.S. Congress, Senate, Commission on Reform and Modernization of the Department of State Act, S 3491, 117th Cong., 2nd sess., introduced in Senate April 6, 2022, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3491/text.