Our Research Agenda

The goal of fp21’s research agenda is to build the intellectual foundation for a new culture of evidence-based foreign policy. Achieving this vision requires us to design our recommendations for reform by studying the best available research and evidence from academia and practice. In that sense, we evaluate the evidence for the use of evidence.

fp21 is different from other foreign policy think tanks. Our research focuses upstream on the processes and operations that the government uses to produce solutions to its policy challenges. We do not proffer on specific policy topics, such as Russian aggression or Chinese competition. Instead, our work seeks to improve how the US government approaches policy decision-making.

Explore our five main research topics below, or jump to learn about how we apply our research.

Designing a new culture of evidence-based foreign policy.

No single intervention is sufficient to change the culture of policymaking in foreign policy. We have designed a holistic approach to reform that breaks the policy process down into its components to allow fp21’s researchers to more thoughtfully develop improvements at every stage of policymaking. To facilitate and organize this work, we have designed a five-stage model of the policy process. This model comprises the five pillars of our research agenda:

- 1.

Information Collection.

Government agencies collect information about the world,

and organize and store that knowledge to make it accessible to others.

- 2.

Analysis.

Officials analyze the collected information to evaluate the

most relevant and pressing issues, describe what is happening in the world,

and predict what will most likely happen in the future.

- 3.

Decision-making.

Decision-makers then design policy options to positively affect the

international environment based upon the best available analysis, and

select the option most likely to succeed.

- 4.

Learning and Accountability.

Officials observe a policy throughout implementation to learn whether or

not it is working. Implementation should be held accountable to clear

standards of success (often called monitoring, evaluation, and learning

in the foreign assistance space). Our policy process should double down

on what works and pivot away from what fails.

- 5.

Workforce and Organizational Change.

Learning from previous stages is fed into back into the people who power

the organization; the most effective employees should be promoted, and

necessary skills should be hired for or trained.

1. Information Collection

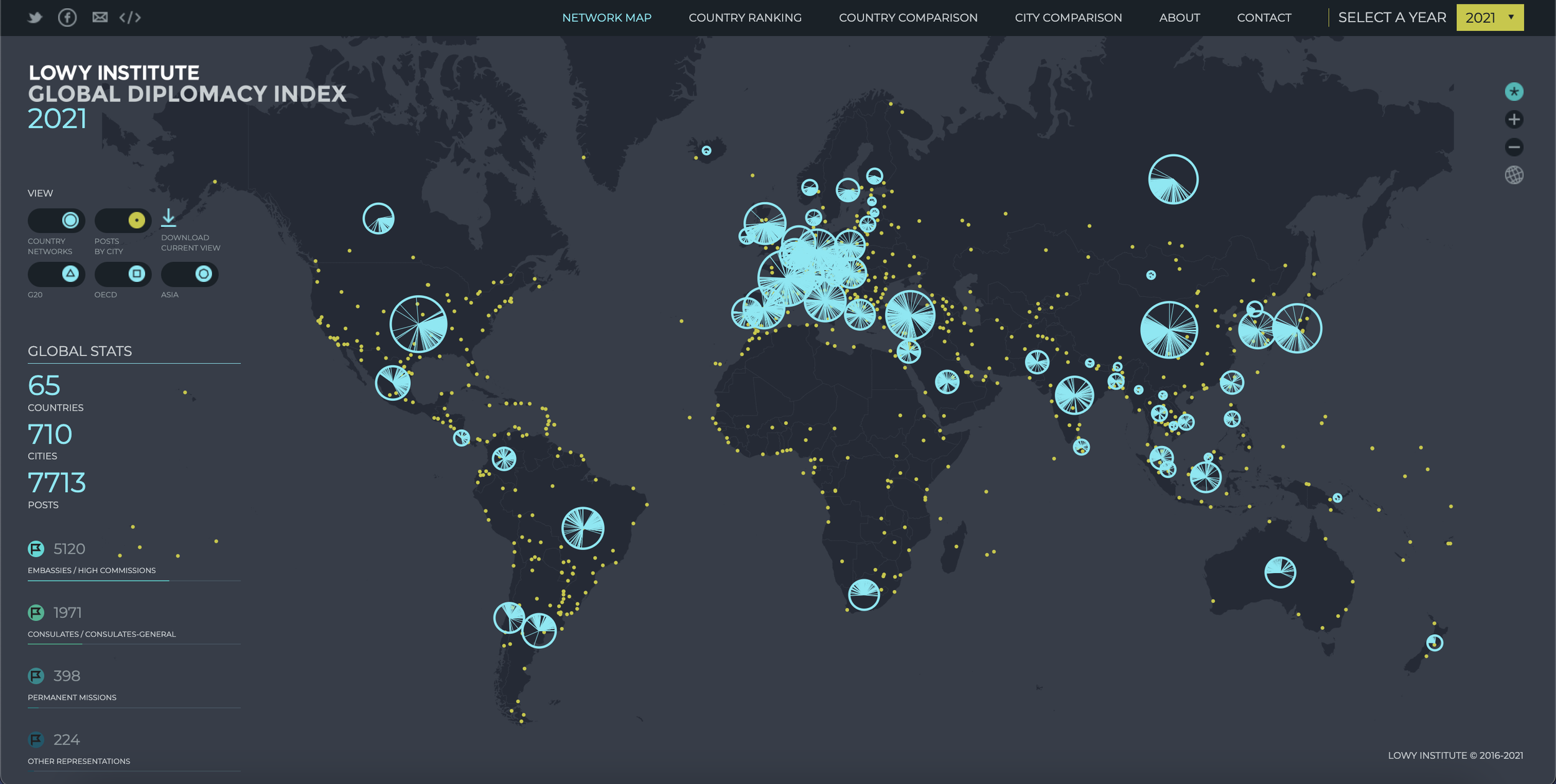

Officials at the State Department have access to vast amounts of information and data, but the information and knowledge management (KM) structures are outdated, undermining effectiveness.

Evidence from industry demonstrates the benefits of improved knowledge management practices are wide-ranging. Research indicates that a robust KM system can reduce information search time by as much as 35 percent and raise organization-wide productivity by 20 to 25 percent.

Unfortunately, the State Department’s knowledge systems have degraded as the volume of information has outpaced legacy processes and systems. Too much of the most useful knowledge fails to reach officials in a timely manner. Key insights may be buried in the avalanche of irrelevant knowledge, forgotten as officials rotate positions, or rendered inaccessible due to stovepiping.

This research pillar comprises how the State Department identifies, creates, captures, acquires, shares and leverages knowledge. These choices have wide ranging implications for policy effectiveness. And yet, efforts to institutionalize strong and effective KM processes in U.S. foreign policy agencies, including the U.S. State Department, remain nascent.

Our research explores the current best practices for enhanced KM in organizations, and identifies recommendations for improved practices for U.S. foreign policy.

Our research questions for Information Collection:

What are the current practices for managing knowledge at the U.S. State Department? What are their strengths and weaknesses, and how are these practices impacting effective foreign policymaking?

What problems can KM practices solve? What resources are required in doing so, and what benefits do they offer? How could KM practices and tools help address current challenges and pain points in U.S. foreign policy agencies?

What are the best practices for KM from various sectors and disciplines? What problems have KM practices solved, and how have they done so?

How might these practices be applied in the context of the U.S. State Department? What are some of the tractable recommendations that could improve current practices?

Explore our publications related to Information Collection & Knowledge Management:

2 & 3. Analysis & Decision-Making

There are at least three types of analysis one can conduct: factual descriptions of what’s happening in the world, explanation of why past events occurred, and prediction of how the world will change. Much of this analysis occurs in the intelligence community, but the best analysis must be integrated into the policy process to be meaningful and effective.

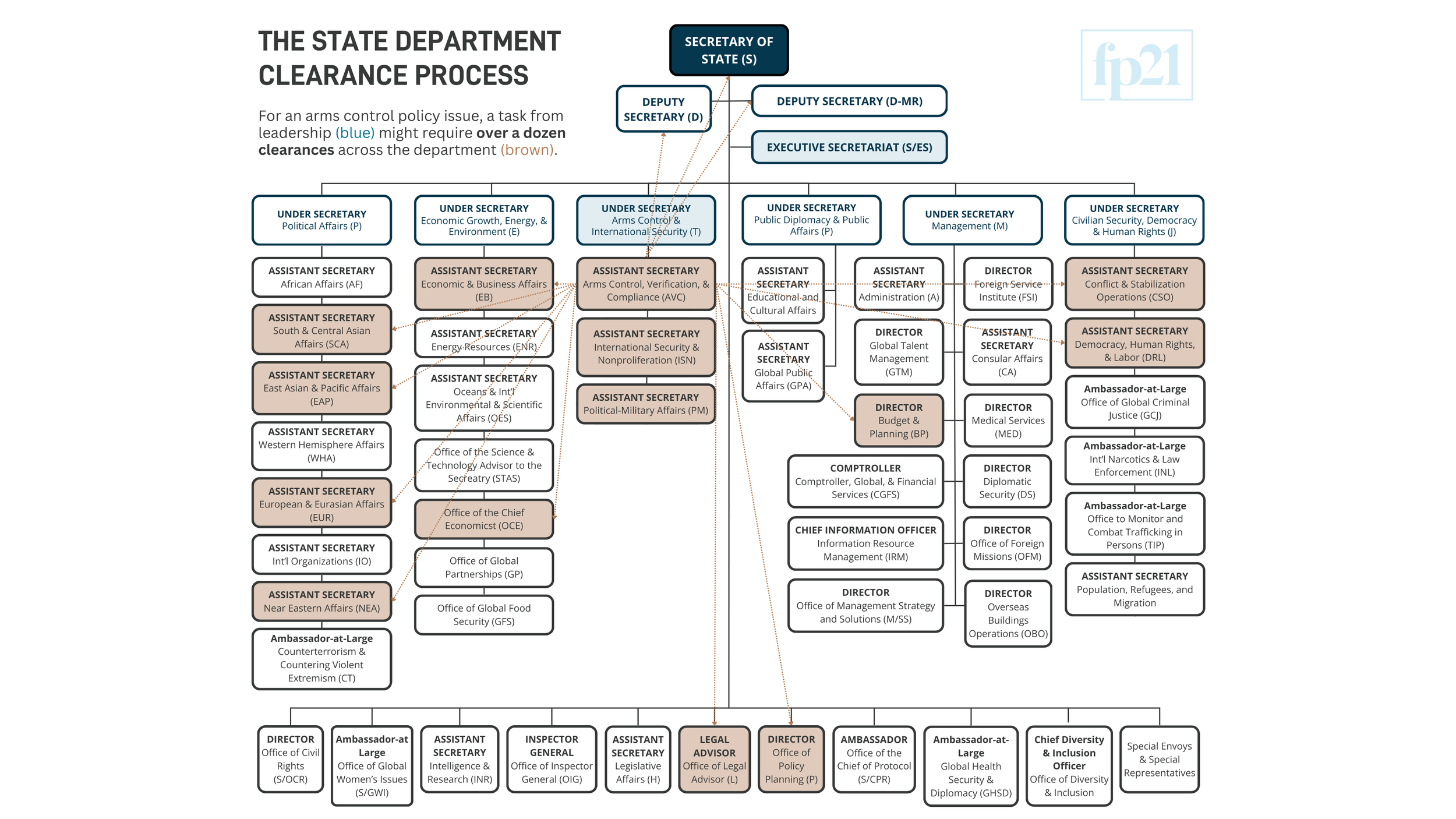

In contrast to the US intelligence community’s rigorous training and standards for good analysis (e.g. IC Directive 203), there are no analytical standards at the State Department, and no methods for distinguishing good analysis from bad. The methods that policymakers use today to conduct and consume analysis are often ad hoc and subjective. Without a process that surfaces and rewards analysis with the strongest evidentiary basis, arriving at good policy depends on the idiosyncrasies of those involved.

Upgrading methods for analysis and decision-making can improve the effectiveness of resultant policy decisions. Our research explores the potential for improving analysis and decision-making processes for foreign policy at the U.S. State Department and other foreign policy institutions. Our work explores learning and evidence on how to upgrade analytical techniques, how to integrate the best available analysis into the policy process, and how to institutionalize processes for longer-term foreign policy planning.

Our research questions for Analysis & Decision-making:

What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing analytical and decision-making processes?

What are the best analytical techniques used in similar circumstances in other organizations and industries? How might these be applied at the State Department?

How can academic research best support the policy process?

What tools, resources and skills are needed for effectively deploying and embedding enhanced analytical capacities in institutions?

What role can forecasting and prediction methods play in policymaking?

How can intelligence and the analysis process be better integrated into policy decision-making?

What are the incentives and best practices for long-term planning within institutions?

What are the most effective approaches to reviewing the quality of policy options, such as red teaming?

How can design thinking be applied to the U.S. foreign policy process?

Explore our publications related to Analysis & Decision-making:

4. Learning & Accountability

Policymaking is difficult. Uncertainty is unavoidable, and one can never be sure exactly how a policy will affect events on the ground. But if the State Department fails to examine a policy’s effectiveness, bureaucratic inertia can sustain a misguided approach for far too long.

Strong organizations learn from today’s successes and failures in order to improve the likelihood of success tomorrow. Fortunately, there are well-developed and tested tools to build a culture of learning. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems generate evidence to allow policymakers to understand the effectiveness of a policy or program from start to finish.

M&E systems also introduce new measures of accountability into bureaucracy. Institutional ties between the White House, Department of State, Congress, and others have grown weak and are often characterized by distrust. These divides need repair. M&E tools rebuild trust by providing ongoing evidence that each organization is working to effectively advance the priorities of our political leadership. Further, M&E frameworks help improve communication of the administration’s policies to Congress and the American people.

The U.S. military leans heavily on after-action reviews, and most government foreign assistance programs already incorporate M&E tools. Yet, strategic-level policymakers rarely use monitoring, evaluation, or learning. In order to support learning and accountability in foreign policy, we must implement systemic monitoring and evaluation standards to support our most important foreign policy initiatives.

Our research questions for Learning & Accountability:

In what settings is M&E appropriate and effective? What problems could it solve for foreign policy, including beyond the programming level?

What are the best practices for organizations to continually learn? In what cases has M&E improved policy and how was this achieved?

What are the best tools and methods for M&E?

What are best practices for integrating M&E capacity into a bureaucracy?

What processes help organizations build more accountability for success?

Explore our publications related to Learning & Accountability:

5. Workforce & Organizational Change

Any improvement of the foreign policy process must begin and end with our most valuable resource: the officials who staff the organizations every day. But the skills commonly associated with foreign policy expertise are highly subjective. For example, the Foreign Service promotes its officers based upon their abilities on a set of “promotion precepts” that include categories such as substantive knowledge and intellectual ability. These qualities are rhetorically admirable but difficult to evaluate. Virtually no training or feedback is offered to improve one’s substantive knowledge or intellectual abilities, which sends the message that great diplomats are naturally gifted. The resulting evaluations are entirely subjective, and there is little ability to compare between officers.

In the absence of more objective understandings of merit, the organization risks hiring or promoting officials for reasons that have nothing to do with their ability to support successful policy.

Improving the recruitment, training and promotion practices for U.S. foreign policy workforces is central to achieving a more effective policy. Merit-based practices which encourage and enable diverse teams can enable more effective workforces to meet today’s foreign policy challenges. Our research explores how U.S. foreign policy agencies can expand and upgrade their training, recruitment and other workforce practices to best serve the needs of a modern and effective foreign policy institution.

Our research questions for Workforce & Organizational Change:

What skills and experience are most required at the Department of State to make successful foreign policy? What skills are most neglected today?

How should the State Department evaluate merit and success of its staff?

What types of recruitment, training and promotion practices will best incentivize a culture of evidence-based policymaking?

What is the role of diversity in evidence-based decisionmaking? What could the State Department do to recruit more diverse workforces?

Explore our publications related to Workforce & Organizational Change:

Research Application: Our Levers of Change

Research is powerless if it is ignored.

To make a difference it needs to be in the right

place at the right time. We have identified five

levers of change as the best opportunities to

get our research to the right place and build the

necessary momentum for reform.

The sector is ripe for change. fp21 is responding to a wave of

calls for better policy-making at the Department of

State. Recent government efforts illustrate momentum

and interest in modernizing and innovating U.S.

foreign policy, including a new Congressionally-sponsored Commission on State Department Reform and Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s

modernization agenda.

Our lines of effort below aim to apply and implement our research agenda:

Mission:Transition

We are building a comprehensive but pragmatic reform agenda for a future Secretary of State to use to empower their department. We call this project Mission:Transition.

The project’s goal is to produce a transition manual for the next presidential administration—a realistic and actionable set of Day One reforms. We hope that our manual can lay the groundwork for a reform-minded administration’s transition into government.

As research on institutional reform indicates, true transformation requires a cultural shift, led by leadership that takes on bold ideas while understanding workplace cultures to encourage true growth and innovation.

Explore our publications related to Mission: Transition:

State Department Learning Agenda

fp21 is collaborating with the State Department to execute its Learning Agenda, which was required by the Foundations for Evidence-based Policymaking Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-435) (“Evidence Act”). The Learning Agenda is a systematic plan to answer a set of policy-relevant questions critical to achieving the agency’s strategic objectives. As the Learning Agenda explains, “The Department of State sees its learning agenda as a way to directly enhance U.S. foreign policy in the twenty-first century, bolstering the Secretary of State’s modernization efforts.”

Congressional Engagement

Congress plays a vital role in US national security. Through authorizations, appropriations, and oversight, the House and Senate shape the structure and budget of the executive institutions that lead our foreign policy. Many reform proposals require Congressional authorization or budgetary support. fp21 takes an active role in engaging with Congress to educate Members and staff about the landscape of foreign policy reform.

Explore our publications related to Congressional Engagement:

Training Curriculum for Diplomats

Most foreign policy officials never receive official training in how to conduct analysis or make decisions. Such techniques are left entirely to the imagination and instincts of each official. But advances in decision science have created opportunities to train the next generation of policymakers with proven techniques to improve the quality of analysis and decisions.

fp21 is developing a curriculum to ensure our foreign policy decision-makers are the best trained in the world.

Explore our publications related to Training Curriculum for Diplomats

Academic Connections

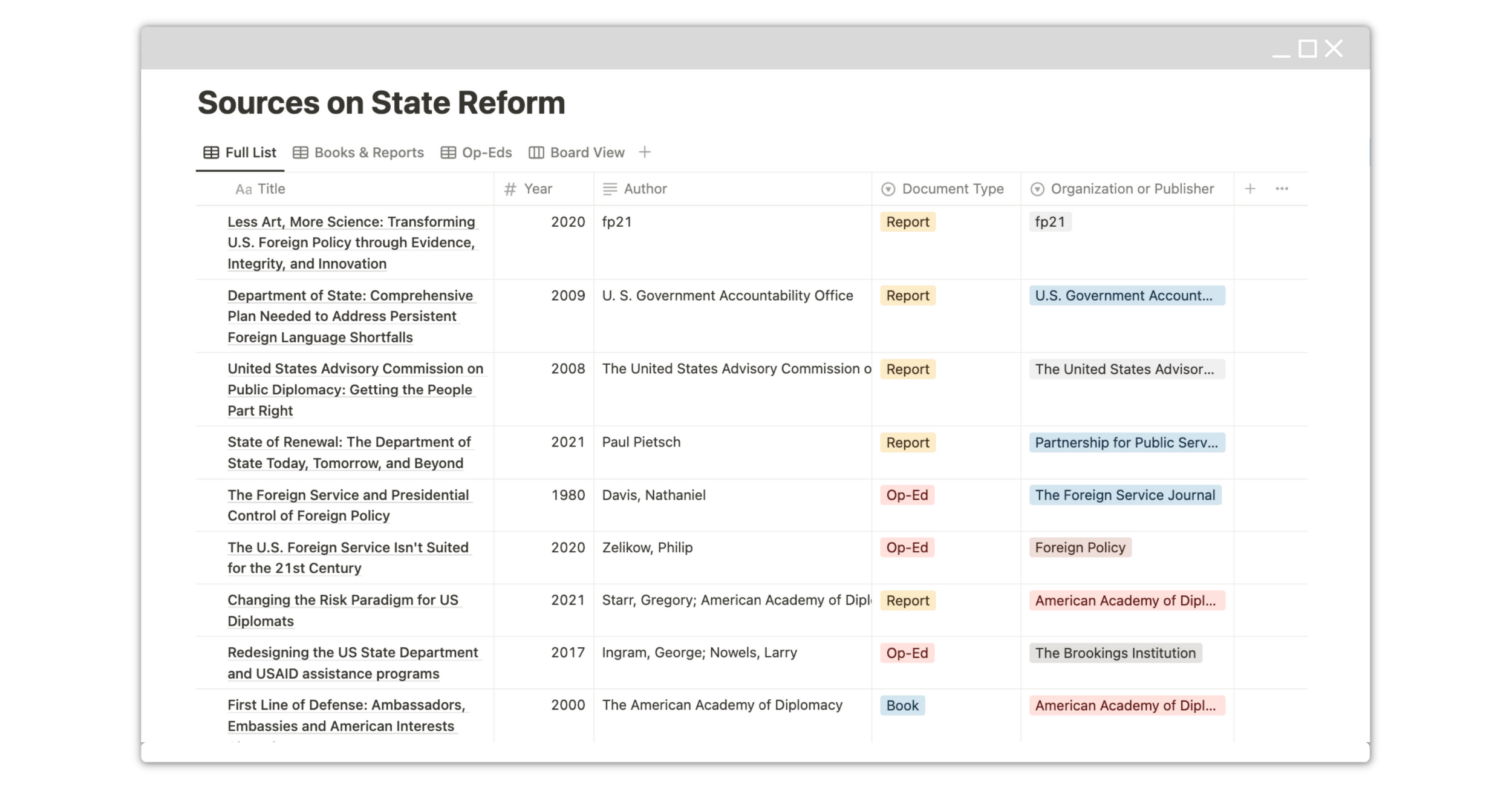

fp21 is building connections with scholars who study the processes and institutions of US foreign policy. By drawing from the best available research and evidence from across a wide variety of academic disciplines, we are building a more effective policy process.

Explore our publications related to Academic Connections

Join our coalition.

Contact Us | Twitter | Newsletter | LinkedIn