The Road to Diversity

An Evidence-Based Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Agenda for the Department of State

April 2022

Introduction

President Biden declared in a February 4, 2021, presidential memorandum,¹ “It is the policy of my Administration to prioritize diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility as a national security imperative, in order to ensure critical perspectives and talents are represented in the national security workforce.” A great deal of attention² has centered³ on the Department of State, where a history of discrimination⁴ laid a foundation for continued inequality.⁵ The appointment of State’s first Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer⁶ and the focus on diversity in Secretary of State Blinken’s modernization initiative⁷ is evidence of the high-level political attention to the issues of discrimination and inequity in the diplomatic establishment.

Achieving sustainable progress at the Department of State requires real political leadership and a coalition that can continue to push for change. But political will alone is insufficient—effective policy interventions need to overcome a legacy of structural racism, sexism, and discrimination in the United States’ first executive agency. There is no silver bullet, and many well-intentioned efforts to improve the diversity of our institutions have fallen short. Progress requires an effective agenda for reform to ensure that goodwill is translated into real action.

This report is an effort to deepen our understanding of the research on workplace diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives and build a strong foundation of evidence for policymakers to use.

This report evaluates the most common recommendations to improve DEI in organizations, categorizing each recommendation based on its likelihood of success according to the research. It provides a blueprint for monitoring and evaluating (M&E) new policies to ensure institutions can learn from what works and dispense with ineffective policies. And this report bolsters the best available research with the perspectives of those most directly impacted by discrimination at the Department of State.

¹ The White House. “Memorandum on Revitalizing America’s Foreign Policy and National Security Workforce, Institutions, and Partnerships.”

² The Truman Center for National Policy. “Transforming State: Pathways to a more just, equitable, and Innovative Institution.”

³ Heath, “The State Department Has a Systemic Diversity Problem.”

⁴ Strano, “Foreign Service Women Today: The Palmer Case and Beyond.”; Christopher, “The State Department Was Designed to Keep African-Americans Out.”

⁵ Government Accountability Office, “State Department: Additional Steps Are Needed to Identify Potential Barriers to Diversity.”

⁶ Blinken, “At the Announcement of Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley as Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer.”

⁷ Blinken, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken on the Modernization of American Diplomacy.”

Key Findings

Three principles emerged from our research:

1. Structural changes are vital. Research suggests that policies work best when they tackle structural changes such as formal procedures and policies, leadership and culture, and organizational incentives. State Department leaders hoping to make progress on DEI must recognize the structural challenges standing in the way of progress. Department of State practices and procedures—especially the recruitment, promotion, and clearance process—have developed under the legacy of systematic racism⁸ that functioned to preserve a largely white and male Department. While sentiments may have changed, the structural legacy of these procedures continue to disadvantage underrepresented groups. Research has outlined how procedures can be applied equally to all employees, but nevertheless result in adverse effects for certain communities.

Individual decision-makers are the drivers of diplomacy. Yet the research on creating lasting change by targeting individuals is underwhelming. Even when implemented effectively, programs that target individual-level remedies work best when they are paired with structural changes.

2. Data is a vital strategic capability for improving DEI. Demographic data is necessary to both diagnose obstacles and create targeted solutions.

Transparency helps create shared identification of problems, convey to employees that diversity is important and will be addressed like any other organizational priority, and create social accountability. This final point is important, as social accountability is vital for reducing bias and discrimination.

Data transparency can also act as a social catalyst for change, leveraging the decentralized structure of the DoS hiring system by encouraging innovation and rewarding success. Individual-level motivators are important—and receiving public credit for these efforts is a way to incentivize individual-level action until they become norms.

3. The Department must build the capability to monitor and evaluate DEI. Effective monitoring and evaluation requires setting clear goals and metrics in order to continually learn about the challenges and opportunities facing our bureaucracy. Not every intervention will be successful, and difficult tradeoffs will be faced along the way. But flying blind is not an option.

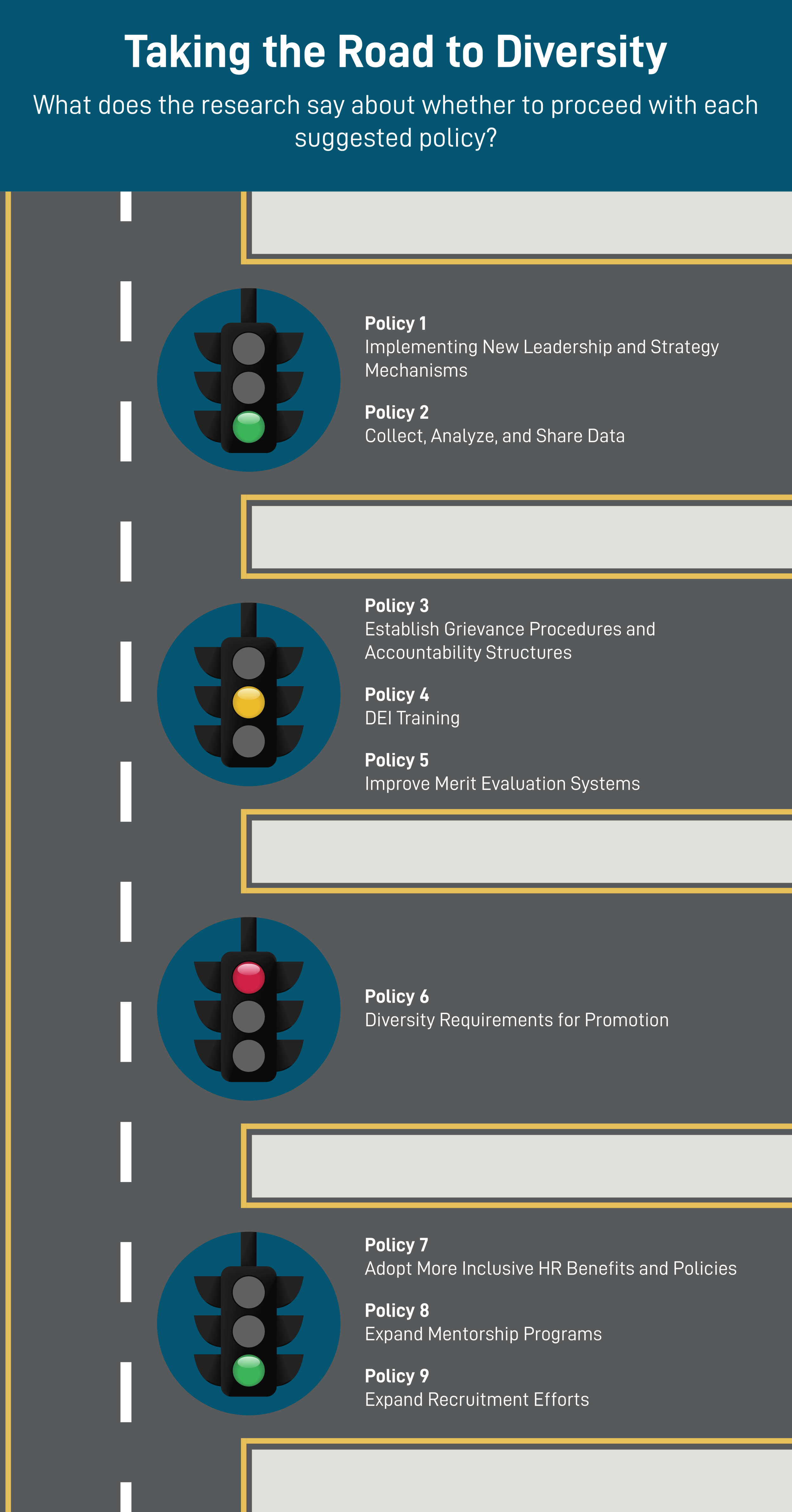

A full summary of our recommendations can be found in figure 1.

⁸ Christopher, “The State Department Was Designed to Keep African-Americans Out.”

Acknowledgements

Morgan Ivanoff led the research and drafting of this report.

On December 18, 2020, fp21 convened leading practitioners, researchers, and analysts to discuss DEI at the Department of State. Since that time, we have engaged extensively with this community. We thank them for their time and contributions to this research, including Dr. Katina Sawyer, Dr. Victor Marsh, and Amy Dahm.

We also acknowledge the many diplomats, advocates, researchers, and community members who have been laboring for many years to overcome systemic discrimination within the institutions of U.S. foreign policy. They have done important and often unacknowledged labor to improve the quality of U.S. national security, sometimes at great personal cost. Their voices and perspectives deserve amplification.

Understanding Diversity

What do Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion mean?

To better understand how to build a more just and effective bureaucracy, let us first define the terms.

Diversity refers to the collection of identities and characteristics that differentiate groups of people from one another. Gender, race, ethnicity, disability, and sexual orientation are all common examples of characteristics used to indicate diversity. It is important to note that people are not diverse, nor is one characteristic diverse. Diversity is a group-level characteristic.

Equity is the ability of all members to have equal access to the opportunities and benefits of the institution: promotion, advancement, recognition, compensation, etc. Creating a level playing field requires systematically addressing the individualized needs of employees to ensure that they can access those opportunities, recognizing that individuals sometimes require different resources to succeed. Individuals do not always start at the same place, and systematic barriers exist that create challenges for groups of individuals as they seek employment opportunities and promotions.

Inclusion is the act of creating a welcoming environment that acknowledges and celebrates the different perspectives and experiences of personnel. To retain diverse teams, and to harness the benefits of diversity, employers need to create an environment in which all employees can thrive. Highly diverse groups are not necessarily inclusive, but employee retention of diverse groups is often seen as a reasonable approximation of inclusion.

A note on accessibility:

Persons with disabilities face barriers to fully accessing and benefiting from equal employment opportunities at the DoS. Accessibility is intrinsically linked with issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. In this report, fp21 highlights the role of collecting data on disability and modernizing HR benefits to better accommodate diverse employees. This report does not summarize and analyze research on accessibility as it relates to the premises and accommodations best situated to advance the hiring, retention, and promotion of persons with accessibility challenges.

Why is DEI a priority focus?

DEI aligns American values with strategic foreign policymaking.

A diverse diplomatic corps is a national security imperative. The skewed demographics⁹ of today’s State Department, especially in leadership ranks, are a legacy of intentional policies aimed at minimizing career opportunities of certain groups or excluding them from service altogether. Rebuilding the meritocracy to reward the most skillful and effective employees will improve the quality of our foreign policy.

Foreign policy is more effective when the diverse experiences of Americans are harnessed to solve complex problems. Scholars have shown that diverse teams tend to lead to more efficient and effective outcomes. Managed properly, diverse teams are smarter and perform better.¹⁰ They can recall facts more accurately, process information more carefully, and are more creative.¹¹

Further, a diverse diplomatic force lends credibility to the American values we promote and legitimizes our efforts to achieve our objectives abroad. In announcing the State Department’s Equity Action Plan pursuant, Secretary Blinken emphasized that “the systematic exclusion of individuals from historically marginalized and vulnerable groups from full participation in economic, social, and civic life impedes equity globally, while fueling corruption, economic migration, distrust, and authoritarianism.”¹² Repressive states abroad have pushed back against international criticism by pointing to U.S. domestic challenges with race. Adversaries have also influenced domestic American politics by inflaming tensions on social media¹³ on polarizing topics such as race and diversity.

fp21 believes that American diplomacy will be stronger when led by a diverse corps of civil and foreign service officers. Investing in DEI improves our national security.

⁹ General Accountability Office, “State Department: Additional Steps Are Needed to Identify Potential Barriers to Diversity.”

¹⁰ Rock, Grant, and Grey, “Diverse Teams Feel Less Comfortable — and That’s Why They Perform Better.”; van Dijk, Van Engen, and Knippenberg, “Defying Conventional Wisdom.”

¹¹ Rock and Grant, “Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter.”

¹² Blinken, “The Department of State’s Plan to Advance Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities in Foreign Affairs.”

¹³ Koppell, Brigety II, and Bigio, “Transforming International Affairs Education to Address Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.”

How do we use the evidence to support DEI policymaking?

Think more like a scientist.

Despite the limitations of research, existing evidence offers a useful guide for decision-making and the field is advancing quickly.

This report evaluates the efficacy of common policy prescriptions and determine their likelihood of success. It considers both experiential and academic evidence in our analysis. It aims to understand not only which policies are effective, but why those policies are effective, so that we can adapt the right components to our unique context.

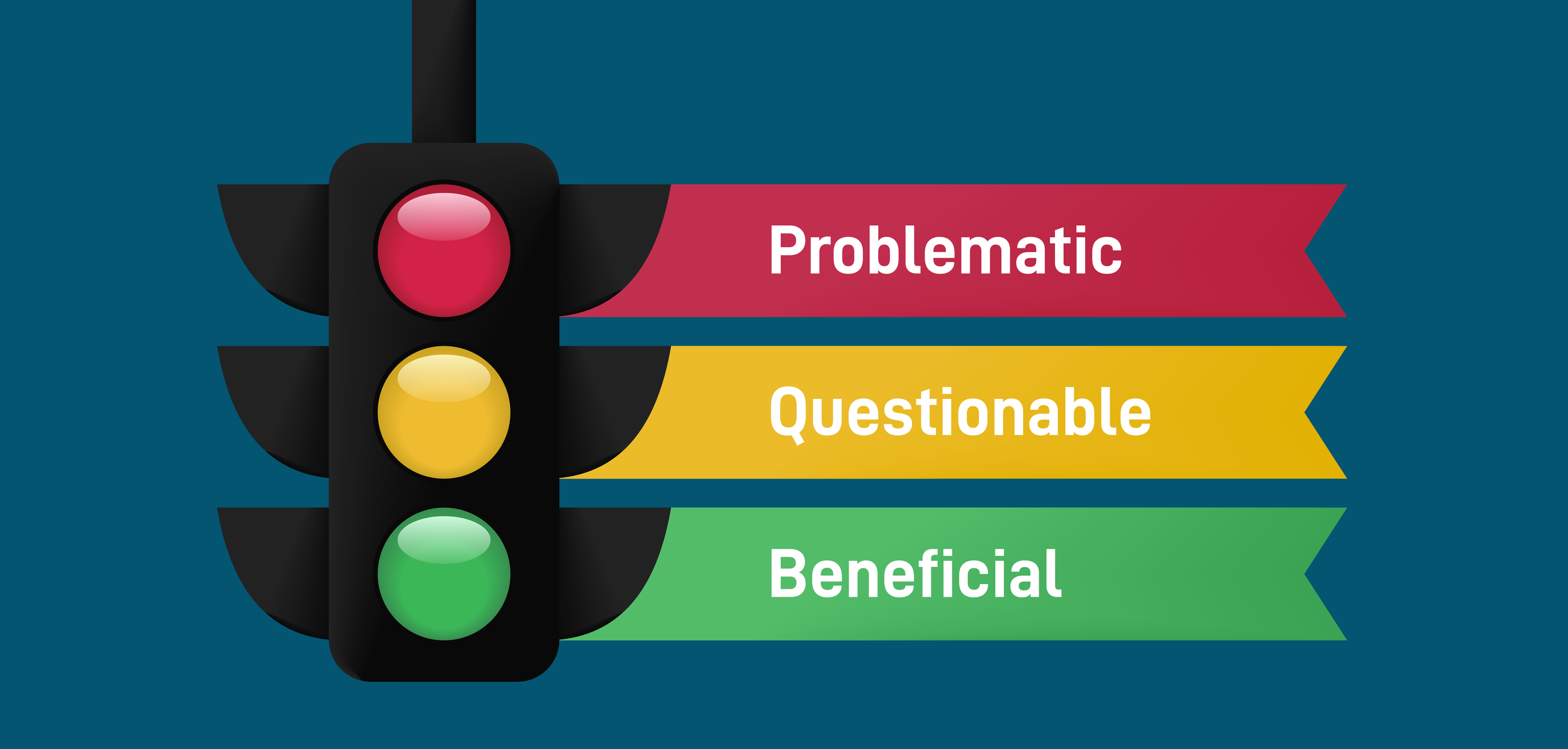

We use a stoplight system to evaluate the likely efficacy of each policy intervention. A green light means “proceed.” It indicates that policies have been shown to improve diversity. A yellow light means “caution”: such policies have limited or mixed evidence about their effects on diversity. Red means “stop”: this policy has not yet demonstrated an ability to positively impact diversity.

This report is not a definitive summary of the research on DEI. Instead, it is intended as a starting point to advance our collective understanding of evidence-based DEI policymaking. Some of the research we survey may be surprising and counterintuitive. Just because a policy intervention has succeeded or failed in the past does not necessarily mean it will be the same in the future. Yet, one should not dismiss robust evidence that challenges expectations. All policymaking requires managing uncertainty, and improving DEI is no different.

Some policymakers believe that shortcomings in research render it unhelpful. These critics prefer to rely on their own instincts about what will work, implying that workforce improvement is more “art” than science. fp21 believes such an approach is shortsighted. While it is important to recognize the limitations of existing research, our knowledge base is nevertheless considerable and offers a useful foundation for decision-making.

We hope our recommendations will guide policymakers as they design interventions. We also want to encourage policymakers to engage more proactively with researchers in this space to encourage more policy-relevant research.

By thinking more like scientists, policymakers in the DEI space must continually strive for better strategies. They must facilitate adaptive learning and continually collect evidence of what works.

As fp21 has written before,¹⁴

“When policymakers demand transparency about the set of facts used to support recommendations and invite scrutiny about potential sources of bias, they make better policy in the present. When decision-makers subject policy recommendations to evaluation and have the courage to change their minds in the face of new evidence, they will make better policy in the future.”

¹⁴ Spokojny and Scherer, “Foreign Policy Should Be Evidence-Based.”

fp21’s Topline Recommendations

Invest in learning and adopt a “Do No Harm” principle.

DEI is an important and timely issue. fp21 recommends committing to adopt policies with strong systems in place to monitor their impact in real-time. Policymakers must be transparent to overcome a legacy of distrust from communities most likely to be affected by these policies and to ensure policies achieve their intended goals.

Monitoring and evaluation systems must collect data and integrate findings into decision-making processes. Good policymaking relies on processes that continually collect and analyze new evidence.

fp21 recognizes that there have been popular policy options that have had unintended outcomes—outcomes that have harmed underrepresented employees. As a result, fp21 advocates for a “do no harm” principle to guide reform efforts. The government should be reasonably confident that an intervention to improve DEI will succeed. If resources do not exist to monitor the implementation of the policy to understand whether it is working, it should not be implemented.

Evaluating the Evidence

The following policy options have all been recommended to policymakers in one report or another. We situate our analysis within the State Department context, indicate what we know from existing evidence, and suggest a path forward.

Figure 1

Chart of policy recommendations and their impact

Policy 1: Implementing New Leadership and Strategy Mechanisms

A Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer is an executive-level position within an organization that is tasked with creating a diversity and inclusion strategy. The authority and scope of this position varies by organization, as do strategy mechanisms for executing DEI-related changes.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: In April 2021, Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley was named the first Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer (CDIO) at the Department of State. The CDIO reports directly to the Secretary of State, Antony Blinken. In an earlier press release, Blinken requested each bureau assign an existing Deputy Assistant Secretary to support a DEI strategic plan and to serve on a Diversity and Inclusion Leadership Council.¹⁵ The CDIO’s preliminary action plan is expected to be released in 2022.

What the working group had to say: Most working group participants welcomed the creation of the CDIO position and were optimistic that Ambassador Abercrombie-Winstanley can foster trust with leadership and make an impact. Some participants nevertheless remain skeptical that the new office will be granted the authority it needs.

The CDIO is housed outside of the existing HR structure at the Department of State. Some participants were concerned about the ability of the CDIO to gain full access to the necessary personnel data owned and maintained by the Bureau of Global Talent Management. Others raised the possibility that the CDIO may be a convenient target for future blame passing. An indicator of success will be whether the CDIO is granted decision-making authority and can gain access to the data necessary to understand the impact of previously siloed DEI efforts operating across bureaus.

What do we know: Strategy mechanisms that establish accountability are important.

There are certain leadership strategies that have been shown to improve organizational diversity. Organizations that establish responsibility structures, for example, see increased diversity within their organizations.¹⁶ Responsibility structures assign employees the responsibility for managing DEI-related issues and hold them accountable for attaining their goals. Relative to other policies that address individual-level biases and social connections (through networking and mentoring, for example), policies that institute organizational responsibility structures are broadly more effective.¹⁷ Responsibility structures, moreover, have been shown to make these other policies more effective.

Research suggests that DEI should be treated as any other organization-wide goal, like increasing profit or producing widgets. To improve DEI, an organization should create goals, establish plans to reach these goals, track their progress, and adapt when changing tactics are necessary. Evidence suggests these approaches also increase diversity in the workplace.¹⁸

Initiatives that engaged with management, such as appointing diversity champions, also positively affected diversity.¹⁹ Initiatives that implicitly or explicitly adopted the assumption that management was the problem tend to have negative effects on diversity.²⁰ Organizations that highlight small wins or elevate the work of diversity champions, can inspire DEI progress across additional areas of the organization.²¹

New leadership mechanisms tasked with supporting DEI can also help foster social accountability within the organization.²² The perception that someone will, or can, oversee individual-level decision-making on DEI-related matters (such as hiring and promotion decisions) can lead to increases in management diversity. Rolling out initiatives in groups has also been shown to be beneficial for creating peer accountability.²³

However, research has not directly shown that CDIOs lead to increases in diversity. One study of higher education institutions found no relationship between hiring a Chief Diversity Officer (CDO) and improved diversity in faculty.²⁴ But research is too underdeveloped to draw confident conclusions.

A path forward: We believe the CDIO will help emphasize DEI as an organizational-wide priority and may be able to make lasting change if given appropriate authority. fp21 recommends the CDIO office develop a monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) framework to support action, planning, and give responsibility for achieving goals to various actors throughout the organization. Transparent planning and communication can also be used to foster social accountability among employees. While direct gains in diversity are an important marker of progress (the proportional increase of women and minorities in each rank and job type), it is also important to recognize that these gains take time. Identifying indicators for short-term behavior and cultural changes can be an important indicator of future success. This framework can also be used to highlight small wins and positive trends and build momentum by rewarding and recognizing personnel responsible for these trends. Individual-level incentives are important to promote good behavior until it becomes a procedural norm. A MEL framework will also be an important tool to ensure that policies do not harm women and minorities, as many have in the past.

We also highlight the strategic value of operating with transparency. Transparency can be used to initiate accountability. Without a transparent plan of action, employees cannot hold leadership accountable, and vice versa. Employees need to understand the DEI goals being pursued, the timeline for reaching these goals, and the actors responsible for achieving these goals, including how the CDIO and other relevant entities, like the Bureau of Global Talent Management, interact and operate. The DEI strategic plan is a great place to start communicating with employees, including the stages and process of planning, the important actors, and small wins along the way.

¹⁵ Blinken, “Investing in Diversity and Inclusion at State.”

¹⁶ Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly, “Best Practices or Best Guesses?”

¹⁷ Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly.

¹⁸ Hirsh and Tomaskovic-Devey, “Metrics, Accountability, and Transparency: A Simple Recipe to Increase Diversity and Reduce Bias.”

¹⁹ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

²⁰ Dobbin and Kalev.

²¹ Nishiura Mackenzie and Wehner, “Context Matters: Moving beyond ‘Best Practices’ to Creating Sustainable Change | Center for Employment Equity | UMass Amherst.”

²² Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

²³ Correll, “SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture.”

²⁴ Bradley et al., “The Impact of Chief Diversity Officers on Diverse Faculty Hiring.”

Policy 2: Collect, Analyze, and Share Data

Organizations use demographic and survey data to track DEI in their organization over time and to identify procedures and practices that may adversely affect DEI throughout the employment pipeline.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: Demographic data is collected regularly on race, gender, ethnicity, and disabilities, disaggregated by rank. Further, Secretary Blinken announced that the Department is “establishing a demographic baseline against which future progress can be measured,” but such data is typically tightly controlled.²⁵ When State’s demographic data is made public, such as in a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) study,²⁶ only aggregated, high-level summaries of the findings are provided, making it impossible for observers to run their own, more in-depth analysis. For example, while the GAO data provides statistics for each rank of the civil and foreign service, one cannot evaluate data by bureau, years of experience, or educational attainment. This makes the identification of specific DEI barriers more difficult.

What the working group had to say: Participants complained about a lack of transparency in State Department diversity numbers: diversity data is not accessible, and what is accessible is not useful. Aggregating data by sex, ethnicity, and race gives little granular information about where problems lie. Participants want to see a more in-depth analysis of diversity that looks beyond rank. Diversity data should be broken down by job, department, bureau, and region. Data should be collected on contractors, as well as permanent employees. Participants also wanted data presented in a machine-readable format. They also highlighted how data is often seen as a tool to point out a problem that is already widely known, when it could be used as a tool to help solve that problem.

Working group participants acknowledged challenges in collecting certain types of data. For example, many people don't self-identify as having a disability.²⁷ Other community members may be reticent to identify as a member of a community that has experienced past discrimination.

What do we know: Collecting diversity data is a powerful tool for change. When data is used to inform decision-making, increase transparency, and hold the institution accountable against an explicit strategy, it can create positive DEI outcomes.

Research suggests that transparency increases equity and diversity by activating social accountability within a workplace. For example, one study showed that when managers were asked to publicly evaluate the progress of women’s careers, women started receiving better assignments and opportunities.²⁸ Another study found that pay disparities decreased when salary decisions were compared and shared with managers.²⁹

Data can also be used as a tool to inspire positive reinforcement by highlighting success. One study found that a small-wins approach can lead to important changes in the short term (cultural changes, individual behavior changes) and spark long-term changes (direct increases in the number of women hired).³⁰ Starting new initiatives with the most engaged actors and offices while highlighting their small wins along the way can catalyze broader change across an organization.

A path forward: fp21 recommends the State Department make a plan to collect and share more extensive demographic data. The plan needs to carefully specify data needs, privacy issues, collection requirements, and the IT infrastructure. Analysis and learning are limited by the quality of the data collected.

More fine-grained statistics should be produced to explain diversity by job title, bureau, region, and pay grade. To increase data available to analysts, fp21 recommends encouraging employees to answer diversity-related survey questions (while preserving the ‘prefer not to answer’ options). The Department should regularly audit its surveys for quality and make improvements both to the instrument and communication strategy.

To increase trust between employees and data collectors, State should be explicit about how the data will be used and why it is important.

The Department of State needs to update and revise exit interviews and employee retention interviews to collect data on why employees are leaving, and why they are staying. To measure inclusion, State should consider collecting data through pulse surveys to understand why people are staying and monitor the impact of DEI initiatives.

Lastly, fp21 recommends publishing more data. Transparency can foster social accountability to reduce individual-level biases. Bureaus, offices, and embassies should publish diversity statistics to highlight successes and failures. State Department leadership should highlight success stories and offer more awards. State must encourage individuals to consciously and continually address DEI until it becomes a procedural norm.

²⁵ Blinken, “Secretary Antony J. Blinken on the Modernization of American Diplomacy.”

²⁶ “State Department: Additional Steps Are Needed to Identify Potential Barriers to Diversity.”

²⁷ “Self-Identification of Disability Form.”

²⁸ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

²⁹ Hirsh and Tomaskovic-Devey, “Metrics, Accountability, and Transparency: A Simple Recipe to Increase Diversity and Reduce Bias.”

³⁰ Correll, “SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture.”

Policy 3: Establish Grievance Procedures and Accountability Structures

Grievance procedures are mechanisms that allow employees to report workplace harassment, discrimination, bullying, and racism to an HR body, typically outside of the normal management structure. Grievance procedures aim to provide resolution for the employee and/or to hold the perpetrator accountable.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: There are three procedures at State that employees can use to report harassment, discrimination, bullying, or racism: grievances, formal EEO complaints, and security-related complaints (referred to as “insider threats”). Data is not shared to indicate how frequent these procedures are used—nor the outcome or effect that each procedure has had on the victim and perpetrator. Employees that have been disciplined are not identified in the promotions and assignments procedures at the Department of State.

What the working group had to say: Participants shared that procedures are often viewed as unable to hold perpetrators accountable or protect victims from further harm. Results of grievance procedures were said to be inconsistent and biased. Some even reported being harmed by procedures intended to help. The procedures can be difficult to navigate, slow or unresponsive, unsupportive and insensitive to victims, and sometimes lead to retaliation against the victim. Even when favorable outcomes were reached, the victim was not made whole and decisions that led to complaints (like a discriminatory hiring decision) were not corrected.

Outside of formal complaint systems, participants talked about the lack of checks and balances on high level managers. Participants reported informal networks of victims helping one another navigate the system in the absence of ¹more clear processes. Anecdotally, victims tend to quit the State Department at high rates.

What do we know: Research on grievance systems suggests the negative experiences of working group members may be fairly common. Studies suggest that grievance processes are often ineffective and inefficient, making it hard to evaluate the impact would be if the systems functioned properly.

Research suggests that the share of women and minorities in managerial ranks of an organization declines by 3-11% after legalistic grievance systems are implemented.³¹ Employees who file harassment complaints have adverse health effects and worse careers over time compared to employees that do not report.³² Nearly half of the formal harassment and discrimination complaints in one study led to retaliation.³³ Harassers were also “more likely to be struck by lightning than to be transferred or lose their jobs,”³⁴ according to one author. Complaints commonly take years to resolve.

Common features that legalistic grievance systems share include a high standard of proof which makes it hard to fire someone, a legalistic process/framework which frames complaints and accusers as a threat, and confidentiality rules such as non-disclosure agreements that protect abusers from pattern detection and facilitate retaliation. There is no research indicating how the observed outcomes may change if these components are eliminated/transformed.

While employers with few women managers generally see significant declines in women’s employment after harassment grievance produces were introduced,³⁵ as more women were hired into management positions, the negative effects decreased. In highly diverse workplaces, the introduction of grievance procedures has no negative effect on gender diversity.

Further, workplaces with more women in managerial positions have fewer cases of harassment in the first place. More women managers, then, decreases the incidence of harassment as well as the adverse effects of grievance procedures.

It is important to note, however, that the effects of women are more complicated when we look at specific groups. White women, for example, experience adverse effects in workplaces with more women.³⁶ This may be due to group threat—as white women make up the most managers, and as a group, they may become a threat when represented in high numbers. As a whole group, however, women do better in both instances when there are more women in the workplace.

There is some evidence that flexible grievance systems³⁷ that provide choices between voluntary and forced dispute resolution mechanisms may support DEI objectives, though the research is limited. These systems move away from a legal format and offer more flexible options to address the various forms of discrimination and harassment.

One such study highlighted how a new grievance system led to a decrease in formal discrimination and harassment filings by 30% by offering mechanisms to resolve cases before they escalate to formal legal complaints.³⁸ If complaints are resolved to the satisfaction of employees, and employees feel safe taking part in systems, then more serious incidents can be avoided.

Diversity managers—designated actors whose specific role is to address and monitor DEI-related metrics internally—have been shown to reduce or eliminate the adverse effects of grievance procedures. In this case, the existence of diversity managers with grievance procedure authority increased the share of Black males but decreased the share of white women, Hispanic women, and Asian men.³⁹ Federal monitoring, an external form of monitoring in which federal regulators review whether contractors are compliant with presidential affirmative action orders, eliminated the adverse effects on all groups except Black men and women.⁴⁰ The mixed results outline why equity is important – different groups need different forms of support at different times in their careers.

A path forward: This research suggests the grievance system in place at the State Department does not meet best practices and could be undermining other DEI efforts. The system requires reform. We commend the Truman Center Report on Transforming the State Department⁴¹ and others for suggesting detailed changes at State.

The Department of State must find a way to prevent serial abusers and bad managers from getting promoted and taking on positions of leadership. The perception that managers learn to “kiss up and kick down”⁴² at State is particularly damning, especially if such behavior turns abusive. Abusive managers should not be tolerated in the Department of State.

³¹ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

³² Dobbin and Kalev, “Making Discrimination and Harassment Complaint Systems Better.”

³⁵ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Sexual Harassment Programs Backfire.”

³⁶ Dobbin and Kalev, “The Promise and Peril of Sexual Harassment Programs.”

³⁷ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Sexual Harassment Programs Backfire.”

³⁸ Bingham, “Mediation at Work: Transforming.”

³⁹ Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev, “Rage against the Iron Cage: The Varied Effects of Bureaucratic Personnel Reforms on Diversity.”

⁴⁰ Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev.

⁴¹ “Transforming the State Department.”

⁴² Martinez Donnally and Le, “Breaking Away from ‘Born, Not Made.’”

Policy 4: DEI Training

A number of organizations run training programs to help educate employees about sexual harassment, discrimination, unconscious biases, and anti-racism. Techniques vary, but each aim to create a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: On September 22, 2020, Former President Trump signed an executive order that banned diversity training. President Biden has since rescinded this ban and issued an executive order calling for expanding access to diversity training for federal employees.⁴³

What the working group had to say: Participants varied in their thoughts on bias and harassment training. Many practitioners felt that training was important because it educated employees on the rules and regulations and created a vocabulary for talking about these topics in the workplace. Some were appreciative that diversity trainers raised awareness and created space for new conversation about workplace culture. Other participants urged caution with unproven training programs.

What do we know: DEI training places the burden on individuals, not the organization itself, to change. While research indicates that the attitudes of individuals can be positively influenced,⁴⁴ it is unclear whether attitudinal change translates into behavior changes, and whether such changes are lasting.

Research on diversity training is mixed. Voluntary training has been shown to have positive results on managerial diversity. Studies find a 9-13% increase in the number of Black men, Hispanic men, and Asian-American men and women in management positions when voluntary training programs are introduced.⁴⁵ Voluntary training signals an internal motivation for training and can frame employees as diversity allies.

Mandatory training, on the other hand, has been shown to have adverse effects on women and minorities. Organizations that require employees to participate in such programs tend to suffer significant drops in minorities in managerial ranks: a 9.2% drop in Black women, 4.5% drop for Asian-American men, and a 5.4% drop in Asian-American women.⁴⁶ Mandatory training instituted to ensure legal compliance and avoid liability, indicating an external motivation for training, frames employees as the problem, a narrative that research indicates may ultimately amplify biases.⁴⁷

These findings suggest that the motivation of the organization and participants can affect the outcome of training.⁴⁸ The curriculum and type of training an organization pursues can signal an organization's motivation for training, which in turn, can influence the management’s commitment to training.

There are some indications of benefits in framing training as “the vast majority of people are overcoming their bias” to avoid normalizing the effects of unconscious bias and educating employees about the negative effects that training can have to overcome false confidence.⁴⁹ Offering options on training may also reduce negative outcomes.⁵⁰

Even the most effectively designed training programs, however, are not showing as strong and consistently positive effects as other DEI policy options, such as mentorship or targeted recruitment programs.⁵¹

In sum, as a mechanism to create larger demographic changes in employees throughout an organization, DEI training alone is not an effective policy option. Researchers’ consensus is that individual-level programs need to be paired with structural changes to create durable progress.⁵²

Sexual Harassment Training: Sexual harassment training has been shown to impact employees unevenly. For instance, when companies institute training programs that focus on forbidden workplace behaviors, a 5% reduction in white women in management was observed on average.⁵³ Such training signals that men are the problem and may lead men to minimize reports of sexual harassment, blame the victim, or harden their views about the acceptability of harassment.⁵⁴ This suggests that sentencing offenders to anti-harassment training may be counterproductive.

Research has identified more effective tools available to employers. Bystander intervention training and training given exclusively to management demonstrate positive outcomes for women and minorities.⁵⁵ Such approaches frame trainees as potential allies rather than potential perpetrators. Employees that take bystander training are more likely to report having intervened in real-life situations, even months after the training.⁵⁶

A path forward: Training is not a silver bullet for discrimination. Generally, training should be voluntary, operate over a longer period of time, and support a larger DEI strategy. Employees and managers should be celebrated as allies that are working towards a common goal rather than framed as the problem.

Because this research is not conclusive on what does work, it will be important to monitor the effects of training over time through additional surveys and data collection.

⁴³ The White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Signs Executive Order Advancing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Government.”

⁴⁴ Chang et al., “The Mixed Effects of Online Diversity Training.”

⁴⁵ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

⁴⁶ Dobbin and Kalev.

⁴⁷ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Doesn’t Diversity Training Work?”

⁴⁸ Kalev and Dobbin, “Does Diversity Training Increase Corporate Diversity? Regulation Backlash and Regulatory Accountability.”

⁴⁹ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Doesn’t Diversity Training Work?”

⁵⁰ Dobbin and Kalev.

⁵¹ Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev, “Rage against the Iron Cage: The Varied Effects of Bureaucratic Personnel Reforms on Diversity.”

⁵² Kalev and Dobbin, “Companies Need to Think Bigger Than Diversity Training.”

⁵³ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Sexual Harassment Programs Backfire.”

⁵⁴ Dobbin and Kalev.

⁵⁵ Dobbin and Kalev.

⁵⁶ Dobbin and Kalev.

Policy 5: Improve Merit Evaluation Systems

Some advocates propose creating standardized and objective measurements of merit within the organization. “Blind” evaluation standards would theoretically create an equal playing field for all officials and eliminate any barriers or biases affecting underrepresented groups. Note that policy 6 differs from this one in that it proposes contributions to DEI as a required skill for employees.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: The promotion system⁵⁷ for foreign service officers at State is driven by the employee evaluation review (EER) process. The “core precepts”⁵⁸ provide the guidelines by which evaluators determine the promotability of foreign service employees. Performance evaluations are narrative-based; the employee receives a few paragraphs of review commentary from their two closest managers and contributes a page of self-review. No evaluation data is collected from one’s peers or subordinates.

Performance reviews are evaluated every few years by a panel made up of other foreign service officers. The review panels read hundreds of files each cycle and select the highest performing officials to promote to a higher rank, which is important as one’s rank dictates eligibility for assignments (which are managed in a separate assignment system).

The assignments process⁵⁹ determines a foreign service officer’s job, which rotates every one to four years. This process works like an internal job market and is driven by an employee’s resume and reputation. Rather than a centralized talent management system, each bureau at State is responsible for hiring new staff each cycle from the pool of available applicants. Better assignments support faster promotion: a coveted assignment may give an employee opportunity to take on higher-profile tasks, support more influential officials, and gain new skills necessary for promotion.

Civil service officers are hired for a specific job. The rank is conferred by that job. EERs thus have little bearing on their promotion prospects. Contractors, subject matter experts (schedule B), and political appointments (schedule C) are increasingly prominent at State, and are selected in noncompetitive processes.⁶⁰

One prominent criticism of State’s evaluation system is that it exposes the gender of applicants. In response, State is piloting a procedural change in the Meritorious Service Increase (MSI) program⁶¹ that give pay increases for exceptional performance. The new procedure creates a gender-neutral and anonymized review of nominations, though the original nomination procedure remains unchanged. Preliminary results in 2019 showed a slight decrease in the number of women and minorities getting MSI awards. The pilot program has been extended to allow for further data collection.

What the working group had to say: Participants complained about the lack of clear standards or objectivity in the promotions process at State. This makes it difficult to identify the qualities with which to compare candidates, especially when past experiences and contexts vary greatly. Further, each reviewing officer is given a great deal of latitude to evaluate what he or she believes constitutes merit. Many advocated for more objective, validated, and comparable evaluations of merit. Participants also debated the logic of removing the markers that identify participants as women or minorities.

What do we know: Biases can creep into evaluation systems in a number of ways.

Evaluation criteria are often selected based upon the traits and characteristics modeled by successful employees. If an organization is dominated by a single group, its evaluation criteria might simply describe that group while excluding traits displayed by underrepresented groups that may have a similar or even greater potential for success. For example, when evaluations like the Foreign Service Officer Test use cultural knowledge to evaluate the suitability of a candidate, the design may systematically favor the dominant group whose culture is reflected in the exam.

Bias in the application of evaluation criteria can also occur. For instance, a test might be administered selectively to minority groups to create an entry barrier, or wrong answers might be used to disproportionately penalize underrepresented groups. In such situations, the application of the evaluation is biased, not necessarily the test itself.

Longitudinal research studies find evidence of both of these forms of discrimination. Taken as a whole, performance rating systems have been shown to be harmful to women and minorities. In one study, the number of white women in management has been shown to drop by an average of 4% after four years following the implementation of standardized performance rating systems.⁶² In another longitudinal study, women and minorities received consistently lower salary incomes, even when they had identical performance reviews.⁶³

When a trait such as leadership is used as criteria, research has shown how this trait is given different point values based on the gender of the employee.⁶⁴ For example, taking charge on a project is seen as a valuable way to express leadership traits. Where men are praised for taking charge, however, the researcher found that women were criticized for this same behavior. In this case, measuring leadership in this manner produces a barrier for women, and introduces bias into the design of the system. Biases were more prevalent in organizations with a clear majority, indicating that traits were exhibited by a narrower set of behaviors.⁶⁵ Men and women reviewers were equally likely to exert gendered biases.⁶⁶

Another experiment suggested that gendered stereotypes influence the feedback that employees receive in their reviews. Men tend to receive specific feedback about their performance, while women receive more vague feedback and negative comments about their personality. This demonstrates how identical performance ratings can lead to different outcomes.

Many scholars have investigated what influences performance reviews. The findings of one study were surprising—bias infected decision-making more when the system explicitly purported to be merit-based. In this case, assigned reviewers in a control group favored men over equally qualified women and gave men 12% higher bonuses.⁶⁷ This was despite candidates having the same performance evaluation scores and the same supervisor. Results for hiring, promotion, and termination decisions were similar. When a system purports to be merit-based and immune to bias, it seems to lead reviewers to stop consciously censoring their internal biases.

Using clear criteria to evaluate employees is not a panacea. The assumption that merit-based evaluations can be immune from bias can be counterproductive.

What works: Research suggests that organizational transparency on processes and outcomes of promotional decisions can elicit social accountability and improve diversity.⁶⁸ One study shows that establishing clear criteria and monitoring the selection and evaluation of criteria can reduce gender bias.⁶⁹ The researcher indicated in her case study that reviewers should provide specific examples of how the candidate exhibited criteria to reinforce intentional decision-making and self-accountability. This tactic is already emphasized in the Department of State’s evaluation system.

Scholars recommend creating a feedback loop to monitor how promotion criteria lead to success within the organization.⁷⁰ Initiatives that limit managerial discretion perform better under external monitoring.⁷¹

Finally, other research shows that redacting the names and genders of candidates seeking a job increases the number of women and minorities who receive interviews.⁷² At the same time, blind interviews may also hinder women and minorities by shielding the discrimination that may have contributed to their employment history. Evaluating personnel as a group (in a comparative manner) is also shown to reduce personal biases in decision-making.⁷³

A path forward: fp21 recommends that the State Department establish a task force to redefine merit and how the characteristics of merits will be used to compare candidates and employees. The task force should include experienced diplomats with diverse experiences and backgrounds as well as researchers who study bias in performance systems. Past evaluations should be analyzed to understand how, and if, criteria interacted with gender norms and racial stereotypes. The workings of the task force should be as transparent as possible and emphasize participation among all affected employees.

Before implementing any new promotion or assignment system, the State Department must commit to carefully study the new option, including treatment and control groups. The success rate of the systems should be compared to evaluate whether one group is hired more, or promoted as often, compared to others. Adjustments should be made to improve the system before rollout.

The task force must also develop a transparent monitoring and evaluation scheme to understand the effects of the promotion process throughout implementation. Monitors should be tasked with interviewing reviewers on the potential biases in their work to improve social accountability.

Finally, State should explore new approaches to the assignment placement system. Research indicates that biases increase when evaluators do not have enough performance information with which to evaluate and hire employees. As the assignments process is separated from the evaluation process, performance evaluation information is not available to a key set of decision-makers that influence the trajectory of an employee’s career.

⁵⁷ “3 FAM 2320 PROMOTION OF MEMBERS OF THE FOREIGN SERVICE.”

⁵⁸ “DECISION CRITERIA FOR TENURE AND PROMOTION IN THE FOREIGN SERVICE.”

⁵⁹ “3 FAH-1 H-2420 FOREIGN SERVICE (FS) CAREER DEVELOPMENT, ASSIGNMENT, AND TRANSFER.”

⁶⁰ “Evaluation of the Department of State’s Use of Schedule B Hiring Authority.”

⁶¹ “3 FAM 4890 MERITORIOUS SERVICE INCREASES (MSI) AND QUALITY PERFORMANCE AWARDS.”

⁶² Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

⁶³ Castilla, “Gender, Race, and Meritocracy in Organizational Careers.”

⁶⁴ Correll, “SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture.”

⁶⁵ Correll.

⁶⁶ Correll.

⁶⁷ Castilla, “Achieving Meritocracy in the Workplace.”

⁶⁸ Castilla.

⁶⁹ Correll, “SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture.”

⁷⁰ Castilla, “Achieving Meritocracy in the Workplace.”

⁷¹ Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev, “Rage against the Iron Cage: The Varied Effects of Bureaucratic Personnel Reforms on Diversity.”

⁷² Gerdeman, “Minorities Who ‘Whiten’ Job Resumes Get More Interviews.”

⁷³ Bohnet and Chilazi, “Overcoming the Small-N Problem, Center for Employment Equity, UMass Amherst.”

Policy 6: Diversity Requirements for Promotion

Evaluating the track record of potential managers in promoting DEI is a common recommendation for organizations seeking to improve their organizational diversity. For instance, applicants for a position might be questioned about their previous interaction with the grievance process or steps taken to meet organization-wide diversity goals.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: The State Department revised its criteria⁷⁴ used to evaluate the tenure and promotion of U.S. foreign service officers in February of 2022, placing great emphasis on one’s impact on diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.⁷⁵ These changes updated the previous evaluation criteria, which asked midlevel officials to “Support equal employment opportunity and merit principles” and senior officials to “recognize that diversity within the workplace is a strategic advantage and act accordingly.” In the words of Secretary of State Blinken, the new criteria signal that “promoting diversity and inclusion is the job of every single member of this department. It’s mission critical.”⁷⁶

What the working group had to say: Underrepresented groups within the Department of State have long-advocated for a way to account for their volunteer work on diversity initiatives. Diversity work was described by some as a “tax” on underrepresented professionals.

Some suggest that the best way to incentivize investments in DEI is to link them to performance.⁷⁷ But others worried that in the absence of checks and balances on personnel, accountability for creating inclusive and equitable workplaces might be rare. There is no system in place to evaluate DEI track records and adverse grievance filings may have a limited impact⁷⁸ on evaluation processes. Some worried about new evaluation standards being gamed or reduced to an exercise in creative writing.

What do we know: The announcement of the new evaluation policy is a first attempt to bring in a systemic approach to integrating DEI into promotions. Evaluation standards are a powerful bureaucratic lever, but research demonstrates that such interventions are often associated with unintended consequences.

Scholarship is cautionary about measuring one’s commitment to diversity in promotion procedures. It is difficult to reliably measure an individual’s commitment to improving diversity outcomes within an organization. Different approaches to evaluating performance have been shown to increase promotion rates for various identity groups, but there is no reliable formula for success. For instance, one study demonstrated that diversity-related promotion incentives increased the promotion of white women by 6%, but decreased the promotion of Black men by 8%.⁷⁹ Another large study corroborated these findings: “These programs did not, on average, increase management diversity,” concluded the authors.⁸⁰

Scholarship suggests that such approaches fail because while the members of a majority group may be rewarded for participation in diversity initiatives, members of minority or disadvantaged groups may be perceived as self-serving for the same activities.⁸¹ Further, diversity evaluations shift the burden of managing diversity from the structural level to the behavior of individual managers.

Researchers note that diversity-related promotion incentives often receive little weight compared with other performance indicators such as sales performance, which dampen the potential positive impact of such measures.⁸² This suggests that diversity may not have been a high priority in the observed organizations and thus unable to change the incentive structures.

A path forward: We labeled Policy 6 with a red light because research suggests this intervention may not achieve its objectives without a holistic plan to address potential shortcomings. Yet we do not suggest the research summarized here is evidence that the policy will necessarily fail. The research cited above was conducted exclusively on private sector firms; public sector promotion standards may work differently.

We intend this red light designation as a signal that leaders must stop and think carefully about how to implement updated performance standards. This policy should be implemented under careful monitoring, and as part of a holistic package of reforms to ensure its intended goal is achieved.

There are compelling reasons to prevent serial abusers of DEI principles from getting promoted. Yet, if other accountability mechanisms such as grievance procedures fail to prevent such behavior, the promotion system will also likely fall short.

Likewise, strengthening DEI performance requirements in the absence of other pro-DEI cultural improvements may do more to encourage employees to game the system for their own benefit than create real progress. Creating a more inclusive culture at the Department of State will require sustained attention and care.

fp21 recommends working with employees to establish their own DEI-related goals in their work plans and demonstrating to promotion panels that such behavior is valued within the Department. The Department should also consider publishing validated guidance on expectations for employees to contribute to DEI to ensure efforts are linked with productive activities. Officials who are successful in promoting DEI should be celebrated by leadership in order to improve social accountability. Wherever possible, efforts should be voluntary and rewarded rather than punitive.

⁷⁴ Department of State Global Talent Management, “Decision Criteria for Tenure and Promotion in the Foreign Service 2022-2025.”

⁷⁵ Vickers, “Thew New Core Precepts and What They Mean.”

⁷⁶ Department of State, “At the Announcement of Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley as Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer.”

⁷⁷ McClure, “The Case for a Foreign Service Core Precept on DEIA.”

⁷⁸ Diplopundit, “FSGB: Selection Boards Cannot Rely Almost Exclusively on Discipline Letters for Low-Ranking.”

⁷⁹ Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly, “Best Practices or Best Guesses?”

⁸⁰ Dobbin, Kalev, and Kelly, “Diversity Management in Corporate America.”

⁸¹ Gardner and Ryan, “What’s in It for You?”

⁸² Dobbin, Kalev, and Kelly, “Diversity Management in Corporate America.”

Policy 7: Adopt More Inclusive HR Benefits and Policies

Modern HR benefits and policies aim to increase inclusion and retention of diverse employees by targeting obstacles that may disproportionately affect individuals from under-represented backgrounds. Examples of modern HR policies include flexible work hours, telework options, continuing education programs, gender-affirming health care, parental leave, spousal support, and child support.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: State has been slow to adopt HR benefits that have been common among many large private-sector employers for several decades. However, the Department of State did adopt 12-week paid parental leave in October of 2020.⁸³ Telework policies, established during the COVID19 pandemic, have remained decentralized, dependent on the individual bureaus and offices, and the future of such policies is unclear. They have not been formalized, despite the accessibility these policies have provided to employees with disabilities and family obligations. Gender-affirming health care was outlined in an executive order by President Biden about advancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.⁸⁴

What the working group had to say: Participants suggested that State Department benefits and policies were often far surpassed by competitors to federal service. The State Department has a reputation for placing the burden of navigating complicated HR rules on the employees themselves. Participants suggested that this expectation needs to be flipped, especially for individuals from underrepresented communities. Participants detailed the need for management to be better trained at integrating available policies into the workplace and making services available to individuals in need. Participants discussed the difficulty of reintegrating employees when their leave is over. Parents returning from leave, for example, felt their promotion prospects diminished. Similarly, those returning from mid-career education programs reported that their new skills were often not valued or utilized.

What do we know: Research has shown that efforts to help employees manage family and life challenges increase retention and support the advancement of women. Benefits such as flexible work hours, parental leave, and childcare support have been proven to help advance the careers of women, particularly women of color, in the workplace.⁸⁵ Parental leave, specifically, has been shown to reduce the pay gap between men and women⁸⁶ and improve the retention of women in the workplace,⁸⁷ increasing gender equality.

While accommodations have overall positive outcomes on diversity, they can also reinforce biases and inequality if not managed carefully.⁸⁸ Workers who pursue flexible work hour accommodations, for example, can be seen as less committed to their work and less suitable for promotion opportunities.⁸⁹ One study found that the type of accommodation used, the parental status, and the gender of the employee can affect promotional outcomes.⁹⁰

Supportive workplace cultures can mitigate these negative effects. A five-year study concluded that employee satisfaction can be increased by redesigning working practices to facilitate working in ways that suit personal and family obligations, and training managers to support individual employees as they exert more control over their time.⁹¹ Best practices identified by researchers suggest managers focus on how work is conducted rather than where and when work is completed.

A path forward: Research points to the positive effects that HR policies can have on increasing diversity. To inform decision-making on which HR benefits will be most beneficial to improve DEI, fp21 recommends the State Department focus on building an evidence-based approach. Management should leverage exit interviews to understand existing barriers, survey employees to identify specific needs, and analyze where in the pipeline employees from diverse backgrounds are leaving in order to effectively target intervention.

⁸³ Richard, “Paid Parental Leave.”

⁸⁴ The White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Signs Executive Order Advancing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Government.”

⁸⁵ Dobbin and Kalev, “Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev Explain Why Diversity Training Does Not Work.”

⁸⁶ Johansson, “The Effect of Own and Spousal Parental Leave on Earnings.”

⁸⁷ Houser and Vartanian, Pay Matters.

⁸⁸ Chung and van der Lippe, “Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality.”

⁸⁹ Kelly and Moen, “Fixing the Overload Problem at Work.”

⁹⁰ Munsch, “Flexible Work, Flexible Penalties.”

⁹¹ Kelly and Moen, “Fixing the Overload Problem at Work.”

Policy 8: Expand Mentorship Programs

Mentorship programs aim to increase the retention and promotion rates of diverse employees by expanding their networks and increasing the information available to them about promotional opportunities. Typically, a higher-ranking mentor matches with a lower-ranking mentee to support their career progression.

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: Formal and informal mentorship programs exist for both the civil and foreign service. In 2018, State HR launched a new program, iMentor, to centralize formal and informal mentoring programs under one program, with more flexibility and resources.⁹² Utilization of the system is thus far unclear.

What the working group had to say: Mentors and sponsors are vital avenues for advancement in the State Department. Job assignments rely largely on a “who you know” system. Women and minorities may face a negative feedback loop: an applicant may be perceived as less qualified if an influential senior official is unable to speak to advocate on their behalf but building a relationship in the first place may be challenging without the benefit of a plum assignment.

It is not clear how effective the formal mentorship program is at forming meaningful relationships. Participants reported experience with poorly qualified mentors, difficulty cultivating relationships across time zones, lack of effective training and guidance for mentors, and a lack of incentives for mentors to participate. We did not speak with anyone who has used the iMentor program; currently, it may be too new to evaluate.

What do we know: Research suggests mentorship programs are among the most powerful tools to increase DEI.⁹³ Formal mentorship programs that match employees with mentors based on shared interests have significantly increased diversity in management positions.⁹⁴ On average, mentorship programs have increased the share of Black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women, and Hispanic and Asian-American men, by 9% to 24%.⁹⁵ Research suggests that men are more likely to be mentored than women.⁹⁶

Mentor-mentee relationships can be evaluated across a wide range of factors including the formality and intensity of the relationship, the rank or demographic difference between mentor and mentee, and the process by which mentor and mentee are matched. There is no perfect mentorship program; different program designs target aim to shape different aspects of an organization’s culture.

Research suggests that the most effective mentor-mentees relationships are between employees who perform similar work within an organization.⁹⁷ By cultivating ties with employees that were at most one level up in the organizations, mentees were able to receive constructive, personalized, and actionable feedback that made a measurable impact on the quality of their work. Close relationships were correlated with faster promotion and higher retention rates than senior-junior mentorship relationships.⁹⁸ Having ties with employees across functional and geographic lines was also an important predictor of advancement and retention.⁹⁹

A path forward: Mentorship programs have created significant gains in diversity at the management level and are one of the best tools for improving DEI in the workplace. fp21 recommends incentivizing mentors and mentees through rewards and recognition, as well as a mentorship outreach campaign to ensure the people who need mentorship the most are appropriately supported.

Mentorship programs must also be properly resourced and implemented. The Department must conduct a needs assessment and periodic reviews to identify ways to monitor and improve programs, recognizing the unique needs of different classifications of employees, including both civil and foreign service officers. We also recommend expanding mentorship relationships to include relationships between peers that are more closely aligned in rank and that operate across posts and regions.

⁹² U. S. Department of State Bureau of Human Resources, “Five-Year Workforce Plan Fiscal Years 2019 – 2023.”

⁹³ Dreher and Cox Jr., “Race, Gender, and Opportunity.”

⁹⁴ Ghosh and Reio, “Career Benefits Associated with Mentoring for Mentors.”

⁹⁵ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

⁹⁶ Nielson, Carlson, and Lankau, “The Supportive Mentor as a Means of Reducing Work-Family Conflict.”

⁹⁷ Cross, “Cultivating an Inclusive Culture Through Personal Networks.”

⁹⁸ Cross.

⁹⁹ Cross.

Policy 9: Expand Recruitment Efforts

Snapshot at State:

What’s happening: A number of programs are focused on increasing recruitment, including the Rangel and Pickering fellowships and the Diplomats in Residence (DIR) program. Recent expansions¹⁰⁰ in these programs have not yet impacted diversity at the higher ranks at the State Department necessary to build a workforce that reflects the diversity of the country it serves.

In the executive order by President Biden on Advancing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Government, Biden asked agencies to reduce reliance on unpaid internships with the aim of increasing equity in recruitment efforts.¹⁰¹

What the working group had to say: While the Pickering and Rangel fellowships have had success bringing diverse talent into the State Department, promotion and retention of these individuals remains well below average. Participants talked about the stigma that follows fellows for having taken a path into the Department some perceive as easier—a stigma that can be attached to minority officers that are not fellows, though they are assumed to be.

Participants discussed expanding the DIR to broaden its scope to reach underserved communities, community colleges, and Native American tribes. The Department should also consider expanding the Hometown Speakers program to turn employees into recruiters and diversity champions, especially employees from underserved communities.

What do we know: Research has shown that recruitment programs for women increase the representation of women in management by 10%—this includes white, Black, Hispanic, and Asian-American women.¹⁰² There are also spillover effects on other demographic groups as well. The share of Asian men in management, for example, increased by 18% after the implementation of recruitment programs targeted at women.¹⁰³ Recruitment programs for minorities have similar effects. Black female managers increased by 9% while the share of Black male managers increased by 10%.¹⁰⁴

Research also indicates how to improve recruitment efforts. Open recruitment is associated with women holding a greater share of management jobs, for example, while recruitment through informal networks has been shown to increase the share of men in management positions.¹⁰⁵ This information can be used to support DIRs in proactively setting up open recruitment events with students. Research also indicates that organizations with formal referral incentive programs achieve greater equity in their hiring systems and see an increase in women in management.¹⁰⁶ Finally, open calls for employment opportunities have been shown to have positive effects for women.

When managers participate in targeted recruitment efforts, they increase their engagement with minorities and women, they learn more about the organization’s specific challenges in recruiting minorities and women, and they become diversity champions.¹⁰⁷

A path forward: We know that treating DEI as any other organizational goal works—and recruitment should not be any different. The Department must set goals, plan, and track metrics to evaluate success.

¹⁰⁰ “The State Department Expands Pickering and Rangel Graduate Fellowship Programs.”

¹⁰¹ The White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Signs Executive Order Advancing Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Government.”

¹⁰² Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev, “Rage against the Iron Cage: The Varied Effects of Bureaucratic Personnel Reforms on Diversity.”

¹⁰³ Dobbin, Schrage, and Kalev.

¹⁰⁴ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Diversity Programs Fail.”

¹⁰⁵ Reskin and McBrier, “Why Not Ascription?”

¹⁰⁶ Dobbin and Kalev, “Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev Explain Why Diversity Training Does Not Work.”

¹⁰⁷ Dobbin and Kalev, “Why Doesn’t Diversity Training Work?”

Conclusion

Observers of the Department of State note a sense of optimism among advocates for reform that has sprung from a rare alignment of political will: Congress, internal forces at the State Department, and the public are all pushing for change. Diversity is being widely discussed as a national security imperative.

Political will, unfortunately, does not automatically translate into lasting change. Even when there is wide agreement on the goal, selecting the right policies to achieve success can be elusive. Therefore, informing policymaking with evidence is so vital. Our institutions must benefit from research and experiential evidence to maximize the efficacy of our policies.

fp21 has sought to understand what works from an empirical view, and why efforts in the past have fallen short. This report is not a comprehensive review of the literature and evidence about DEI interventions, nor is it the last word on what works. Instead, it is intended to lay a foundation for ongoing conversation and study about how to achieve this national security priority.

Bibliography

Bingham, Lisa B. “Mediation at Work: Transforming Workplace Conflict,” IBM Center for the Business of Government, October, 2003. https://www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/Mediation.pdf.

Blinken, Antony. “At the Announcement of Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley as Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer.” United States Department of State, April 12, 2021. https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-the-announcement-of-ambassador-gina-abercrombie-winstanley-as-chief-diversity-and-inclusion-officer/.

———. “Investing in Diversity and Inclusion at State.” United States Department of State, February 24, 2021. https://www.state.gov/investing-in-diversity-and-inclusion-at-state/.

———. “Secretary Antony J. Blinken on the Modernization of American Diplomacy.” United States Department of State, October 27, 2021. https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-on-the-modernization-of-american-diplomacy/.

———. “The Department of State’s Plan to Advance Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities in Foreign Affairs.” United States Department of State, April 14, 2022. https://www.state.gov/the-department-of-states-plan-to-advance-racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved-communities-in-foreign-affairs/.

Bohnet, Iris, and Siri Chilazi. “Overcoming the Small-N Problem | Center for Employment Equity | UMass Amherst.” Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.umass.edu/employmentequity/overcoming-small-n-problem.

Bradley, Steven W., James R. Garven, Wilson W. Law, and James E. West. “The Impact of Chief Diversity Officers on Diverse Faculty Hiring.” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 3, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24969.

Castilla, Emilio J. “Achieving Meritocracy in the Workplace.” Accessed September 24, 2021. https://ideas.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Meritocracy-and-Privilege_Castilla-2016.pdf.

———. “Gender, Race, and Meritocracy in Organizational Careers.” AJS; American Journal of Sociology 113, no. 6 (May 2008): 1479–1526. https://doi.org/10.1086/588738.

Chang, Edward H., Katherine L. Milkman, Dena M. Gromet, Robert W. Rebele, Cade Massey, Angela L. Duckworth, and Adam M. Grant. “The Mixed Effects of Online Diversity Training.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 16 (April 16, 2019): 7778–83. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816076116.

Christopher, Richardson. “The State Department Was Designed to Keep African-Americans Out.” The New York Times. June 23, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/opinion/state-department-racism-diversity.html.

Chung, Heejung, and Tanja van der Lippe. “Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction.” Social Indicators Research 151, no. 2 (September 2020): 365–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x.

Correll, Shelley J. “SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture: Reducing Gender Biases In Modern Workplaces: A Small Wins Approach to Organizational Change.” Gender & Society 31, no. 6 (December 2017): 725–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217738518.

Cross, Rob Cross, Kevin Oakes, and Connor. “Cultivating an Inclusive Culture Through Personal Networks.” MIT Sloan Management Review. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/cultivating-an-inclusive-culture-through-personal-networks/.

American Foreign Service Association. “DECISION CRITERIA FOR TENURE AND PROMOTION IN THE FOREIGN SERVICE,” April 16, 2013. https://afsa.org/sites/default/files/2013coreprecepts_0.pdf.

Dijk, Hans van, M. Van Engen, and Daan Knippenberg. “Defying Conventional Wisdom: A Meta-Analytical Examination of the Differences between Demographic and Job Related Diversity Relationships with Performance.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 119 (September 1, 2012): 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.06.003.

Diplopundit. “FSGB: Selection Boards Cannot Rely Almost Exclusively on Discipline Letters for Low-Ranking.” Accessed March 24, 2022. https://diplopundit.net/2021/12/16/fsgb-selection-boards-cannot-rely-almost-exclusively-on-discipline-letters-for-low-ranking/.

Dobbin, Frank, and Alexandra Kalev. “Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev Explain Why Diversity Training Does Not Work.” The Economist. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2021/05/21/frank-dobbin-and-alexandra-kalev-explain-why-diversity-training-does-not-work.

———. “Making Discrimination and Harassment Complaint Systems Better” Center for Employment Equity, UMass Amherst. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.umass.edu/employmentequity/making-discrimination-and-harassment-complaint-systems-better#overlay-context=collecting-lgbt-data-diversity-initiating-self-id.

———. “The Promise and Peril of Sexual Harassment Programs.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 25 (June 18, 2019): 12255–60. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818477116.

———. “Why Diversity Programs Fail.” Harvard Business Review, July 1, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail.

———. “Why Doesn’t Diversity Training Work?” Anthropology Now 10, no. 2 (2018): 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2018.1493182.

———. “Why Sexual Harassment Programs Backfire.” Harvard Business Review, May 1, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/05/why-sexual-harassment-programs-backfire.

Dobbin, Frank, Alexandra Kalev, and Erin Kelly. “Diversity Management in Corporate America.” Contexts 6, no. 4 (November 1, 2007): 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2007.6.4.21.

Dobbin, Frank, Daniel Schrage, and Alexandra Kalev. “Rage against the Iron Cage: The Varied Effects of Bureaucratic Personnel Reforms on Diversity.” American Sociological Review 80, no. 5 (n.d.): 1012–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122415596416.

Dreher, George F., and Taylor H. Cox Jr. “Race, Gender, and Opportunity: A Study of Compensation Attainment and the Establishment of Mentoring Relationships.” Journal of Applied Psychology 81, no. 3 (1996): 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.3.297.

“Evaluation of the Department of State’s Use of Schedule B Hiring Authority.” Office of Evaluations and Special Projects. Office of Inspector General United States Department of State, February 2019. https://www.stateoig.gov/system/files/esp-19-03_0.pdf.

Gardner, Danielle M., and Ann Marie Ryan. “What’s in It for You? Demographics and Self-Interest Perceptions in Diversity Promotion.” Journal of Applied Psychology 105, no. 9 (2020): 1062–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000478.

Gerdeman, Dina. “Minorities Who ‘Whiten’ Job Resumes Get More Interviews.” HBS Working Knowledge, May 17, 2017. http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/minorities-who-whiten-job-resumes-get-more-interviews.

Ghosh, Rajashi, and T. Reio. “Career Benefits Associated with Mentoring for Mentors: A Meta-Analysis,” 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2013.03.011.

Heath, Ryan. “The State Department Has a Systemic Diversity Problem.” Politico, March 16, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/03/16/state-department-diversity-problem-476161.